History of the Modern Graphics Processor, Part 5

In the 4th installment of the history of the modernistic graphics processor, we had reached a betoken where the market consisted of three competitors: AMD, Intel, and Nvidia. Past 2022, all were following a similar path for their architecture design and all were targeting PCs and workstations. This was dictated by the management that rendering was taking, the requirements laid down by graphics APIs, and broader application of GPUs into compute and AI.

However, in the post-obit years, graphics processors would become i of the largest, most complex, and most expensive components that could exist establish in nearly any calculating device.

...in the following years, graphics processors would go one of the largest, virtually complex, and near expensive components that could exist found in almost any computing device.

Something old, something new, plus a nice lawsuit to kick

In 2022 nosotros saw new architectures released by most of the major vendors, likewise as a slew of products using older technologies. In the case of AMD, their line-upwardly consisted of well-nigh entirely previous systems. In the desktop market place, we were given models using Graphics Core Adjacent (GCN) 1.0 and the even older TeraScale 2 architecture. A good case of the erstwhile was the Radeon R9 280, released in March.

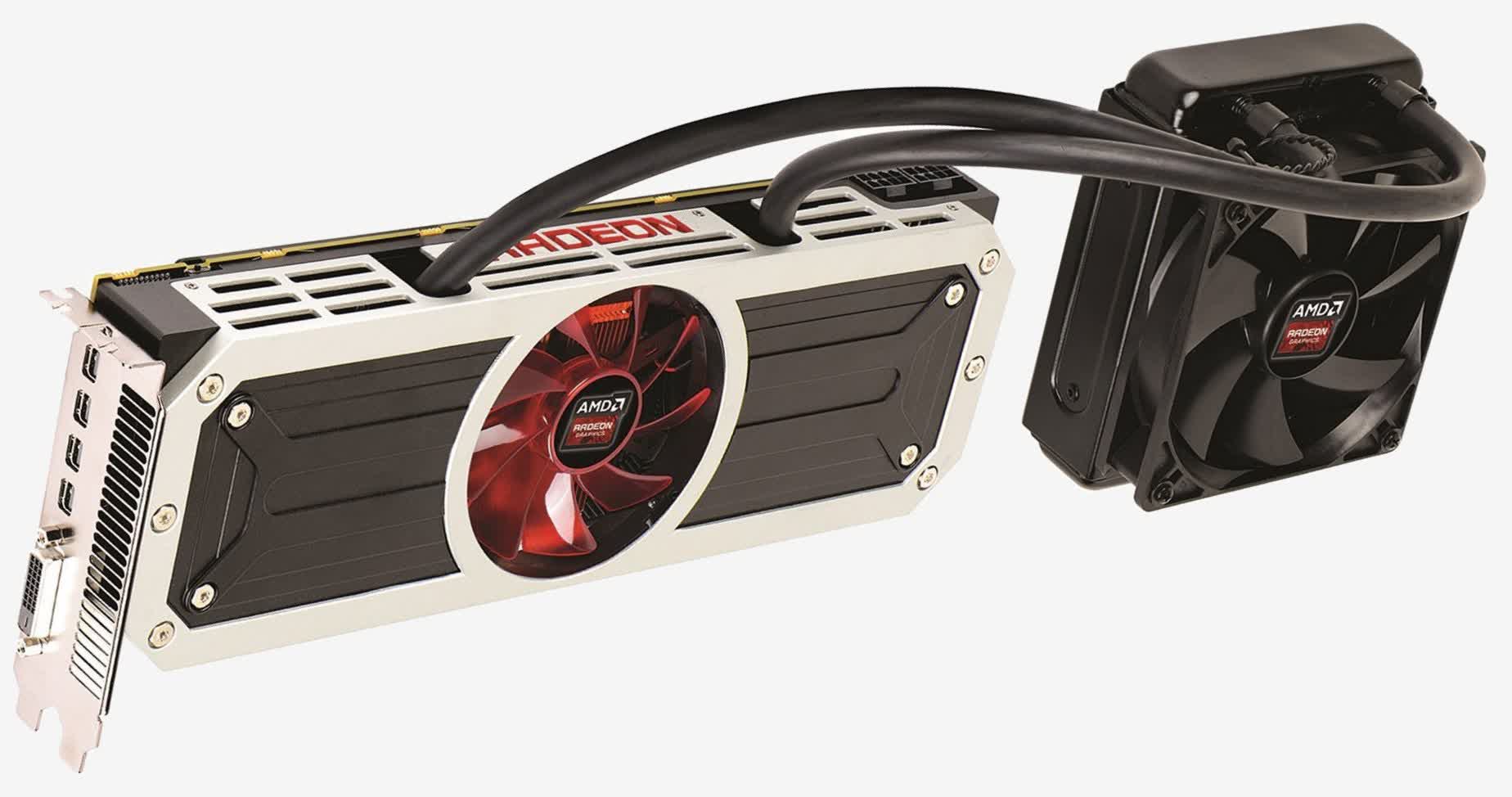

This was a rebranded Radeon Hard disk drive 7950, from two years earlier, merely at least AMD had the sense to launch at a lower price compared to its first iteration. Not long after that production, GCN 2.0-powered Radeon R9 295X appeared and it was very the polar opposite to the 280.

Sporting two GPUs, a custom water-cooling system, and a toll tag of $1,499, it jumped straight to the acme of the operation tables, and nosotros were pleasantly surprised at how good it was (despite its staggering cost).

In September 2022, AMD released the Radeon R9 285 -- this card sported a new chip, with a refresh of their GCN architecture, that brought minor improvements in the enshroud and tessellation systems to the tabular array. At $250, it was pitched at replacing the old R9 280, and came with higher clocks all round. It was simply marginally faster, though, due to having 25% less retention bandwidth.

Information technology might seem odd that AMD made such little progress with GCN 3.0 but at the time, they were struggling with large debts and poor levels of operating income; to combat this, they focused on more assisting markets, such every bit depression power systems and semi-custom designs.

In contrast, Nvidia's fortunes were largely buoyant that year. They made a steady gain in both revenue and net income, despite some odd decisions about products. Like AMD, they used older systems, refreshed ones, and a new compages (Maxwell) -- in the case of the latter, it wasn't used in a tiptop-end, halo model, but instead came to light in a $150 mid-range offering.

The GeForce GTX 750 Ti was designed to compete against the likes of AMD'southward Radeon R7 265. Despite the new tech, it generally wasn't equally fast as the Radeon. Had that been all Nvidia offered in February 2022, one might have thought they were losing momentum.

This was compounded because to no fanfare whatever, Nvidia refreshed their best-of-the-best line -- the GeForce GTX Titan -- with the simple improver of the give-and-take 'Black' and a slightly college clock speeds. At $999, it was no more expensive than its forefather, only it was hardly making the news headlines.

To combat AMD's Radeon R9 295X2 launch in April, Nvidia brought out the Titan Z in the following month. Every bit an practice in pure hubris, it garnered huge amounts of attending for all the wrong reasons.

Hardly any samples were issued to reviewers to clarify, and none were willing to personally shell out for the $2,999 asking cost. For the few that did manage to examination it, the overall functioning was less than ideal for such an expensive product -- generally worse than the the R9 295X2 and two of Nvidia's older GeForce GTX 780 Ti cards in SLI.

Matters profoundly improved in September, when the GeForce GTX 900 series arrived in stores, even though only two models were bachelor.

The GeForce GTX 980 and 970 sported Maxwell-based chips, albeit with pocket-sized tweaks, and went on to grab numerous headlines. The first of which were almost the prices: at $529 and $329 respectively, the new models were both cheaper than the GTX 780 and 770 at launch. Performance was skilful, being competitive confronting AMD's offerings and Nvidia'due south own back catalogue.

All in all, it should have been a successful stop to the year for Nvidia, but the GTX 970 was hiding a 'characteristic' that would quickly undo all of the good press that the launch of the new serial had accrued.

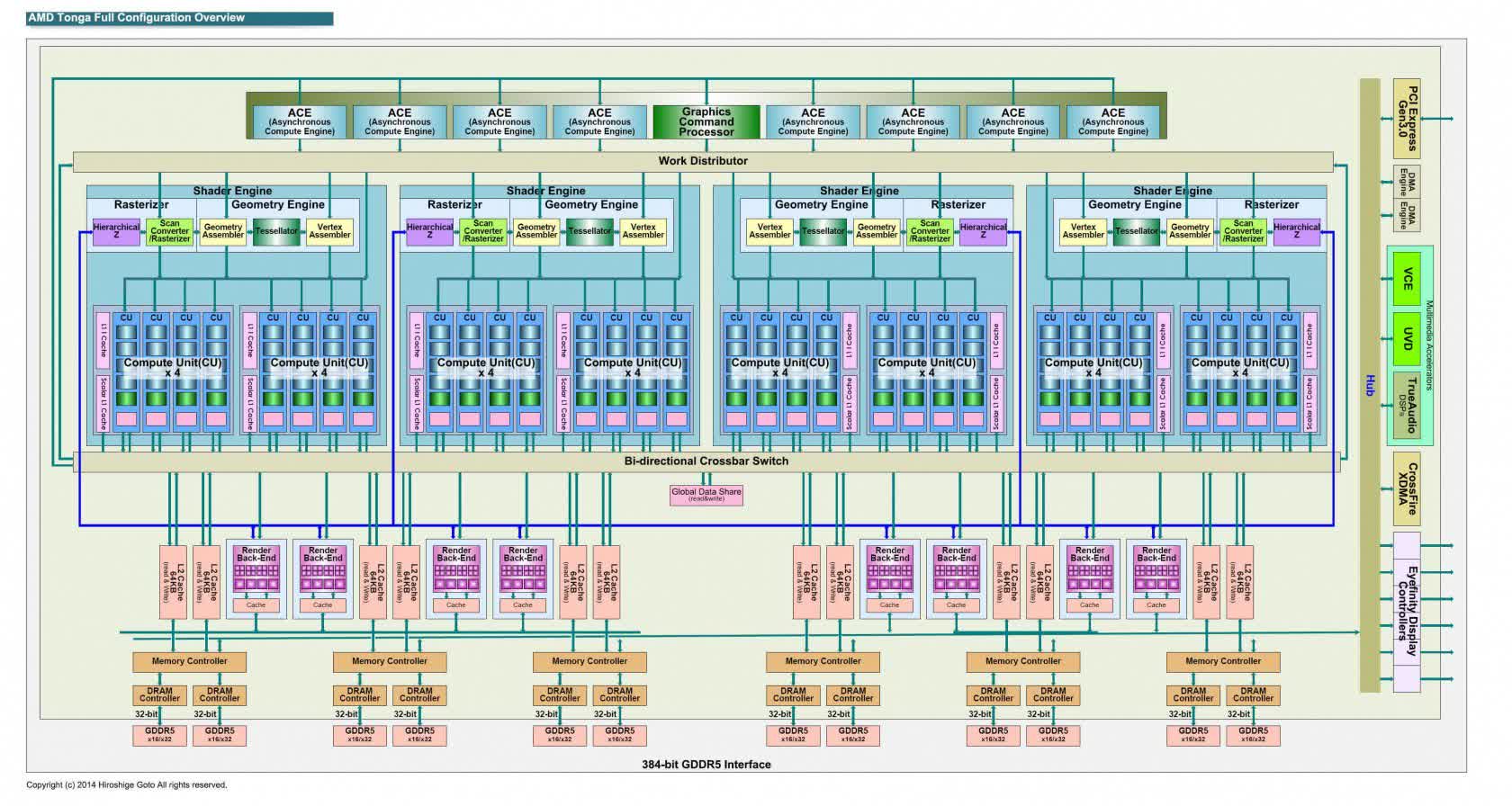

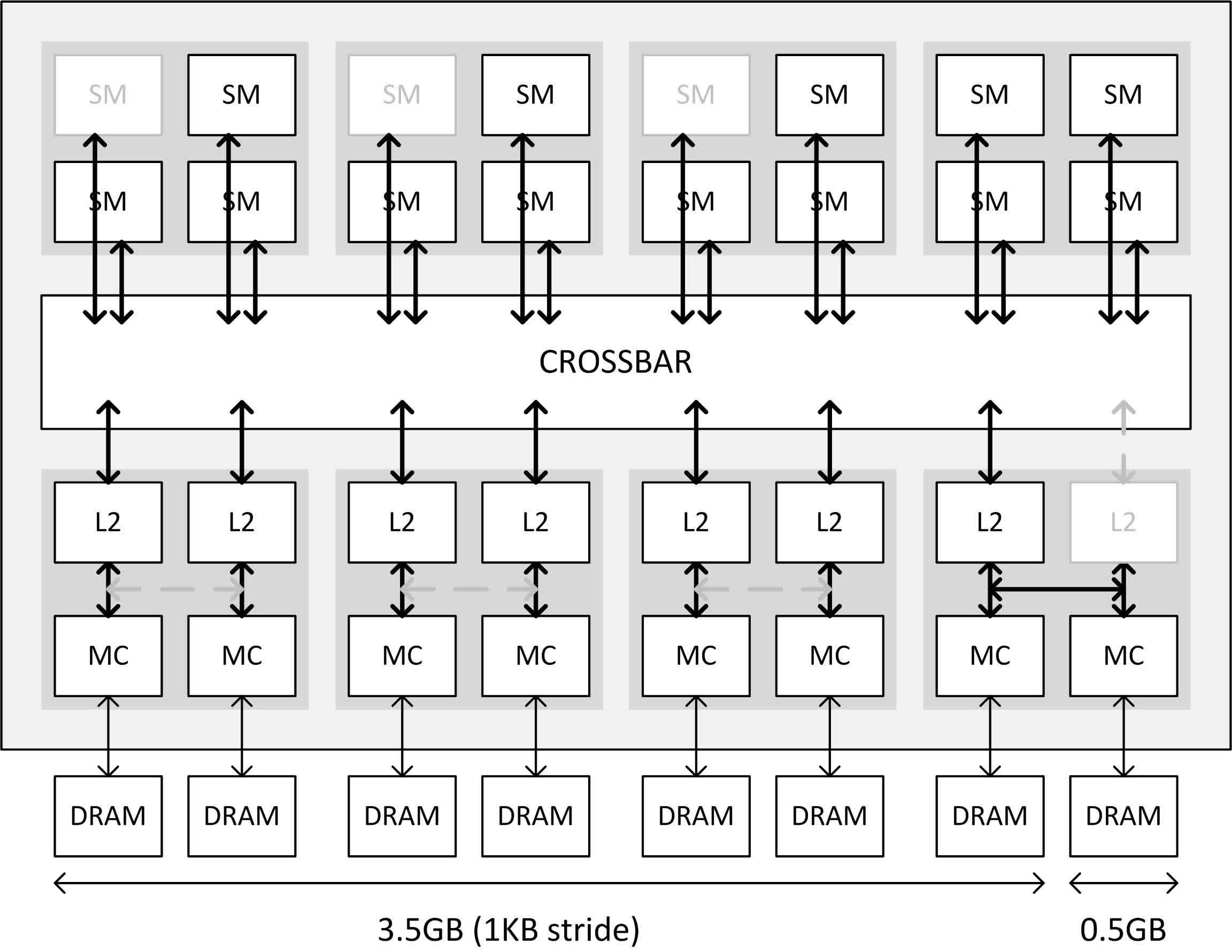

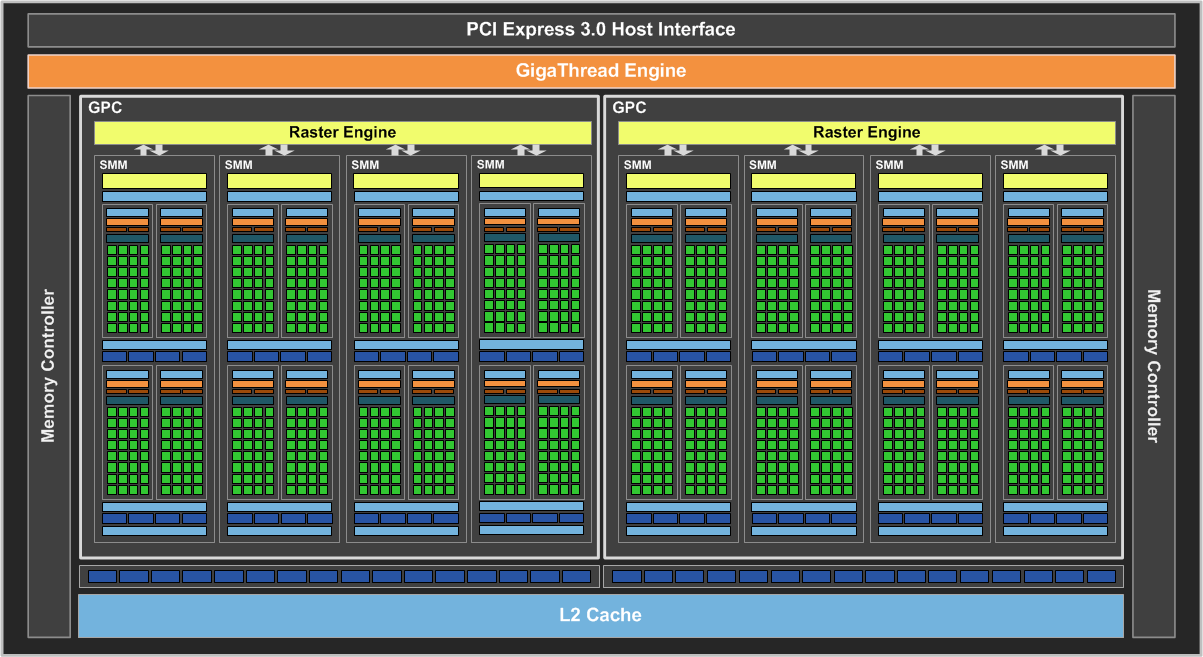

The model's specification sail stated that it had 4 GB of seven Gbps GDDR5 retentivity on a 256-fleck bus -- to all intents and purposes, the same as on the GTX 980. The details tied in with the claim that the GPU sported 64 ROPs (return output units) and 2 MB of L2 cache.

However, what Nvidia kept serenity well-nigh was that this wasn't entirely truthful -- it only had 56 ROPs and ane.75 MB of L2 enshroud, which meant that the retentivity passenger vehicle should have only been 224-fleck and thus merely of 3.5 GB of RAM. So where was the other 0.5 GB?

It really was in that location, so it was "4 GB on a 256-bit motorbus", but non in the same fashion as in the GTX 980. Due to the configuration of crossbar ports and memory controllers, the system could read/write in parallel across the 224-fleck connection to the iii.five GB or use a single 32-bit jitney for the remaining 0.5 GB.

As news of this apparent deception came to light, Nvidia scrambled to explain the situation, blaming information technology on errors in the publishing of their documents for the press.

They provided an explanation for the setup (equally detailed in the to a higher place epitome) and apologized for the mistake, pointing out that the ROP+retention configuration wasn't actually a problem, and was fully intentional. But the damage was washed, and two years later, they were forced to offer bounty to numerous course activeness lawsuits, and publicly offered $xxx to all GTX 970 purchasers.

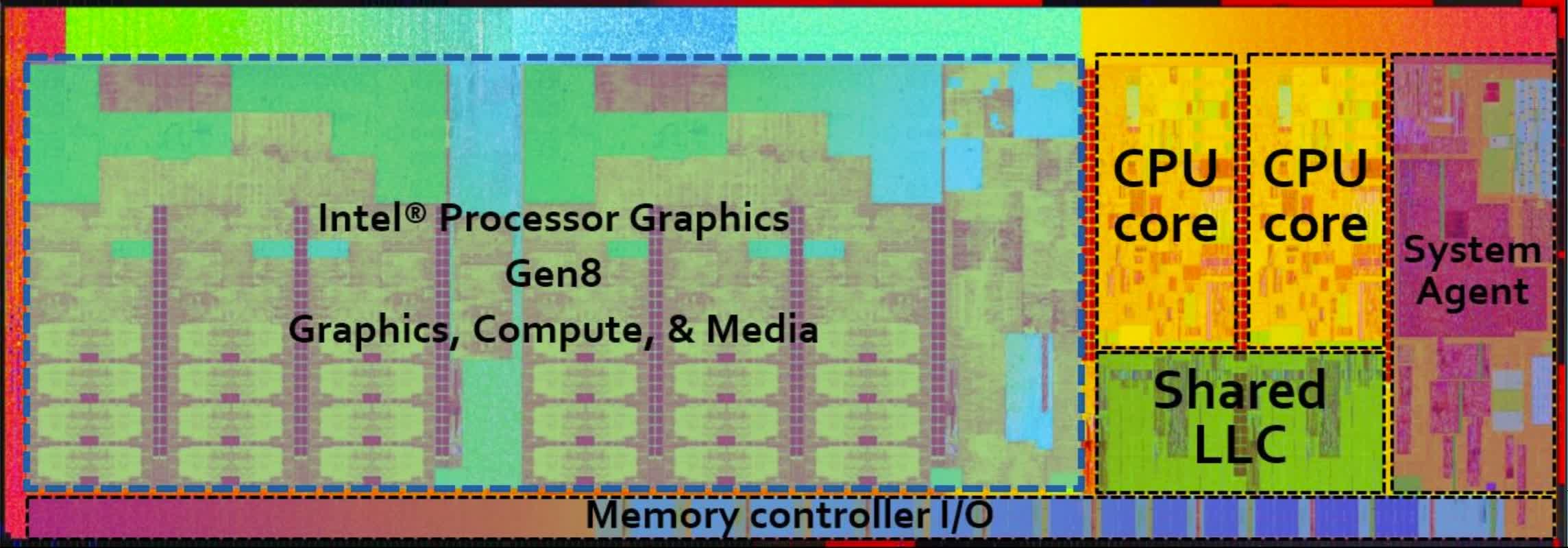

Intel likewise released a new architecture during 2022, codenamed Gen8, equally a core part of their Broadwell-range of CPUs. Integrated GPUs almost never garner any interest, despite existence such a significant portion of the CPU die, only the design marked some notable improvements over its predecessor.

Both pairs of SIMD (single instruction, multiple data) processors in the EUs (Execution Units) could now handle integer and floating point operations, whereas it was just the 1 previously. The effective doubling of the integer throughput rate was matched by providing support for FP16 data formats -- again, at a doubled rate.

These changes brought the tiny GPUs in touch with the architectural capabilities of AMD and Nvidia chips -- however, the paucity of EUs, texture units, and ROPs withal made them unsuitable for gaming.

Not that small GPUs aren't capable of running decent looking games...

In the smartphone world, Apple launched the iPhone 6 in September, powered by their internally designed A8 SoC (organization-on-a-fleck). This processor used licenced CPU and GPU structures from Arm and PowerVR, but the latter also contained some custom units fabricated by Apple tree themselves.

Apple tree was debuting their new Metal API. This collection of libraries included graphics and compute shaders, all heavily optimized for the GPUs in iPhones and iPads. As developers became more familiar with the software over time, it gave Apple's products a singled-out operation advantage over the contest.

The demand for better programming control and low-latency libraries wasn't merely restricted to smartphones. Behind the scenes, the Khronos Group (a consortium of industry bodies) began work on creating the successor to OpenGL -- the aim beingness to provide a cross-platform graphics and compute API, based on AMD'south piece of work with their Pall software.

And software was to become a critical characteristic of the following yr.

Something old, something new... wait, this again?

In many ways, 2022 was just a repetition of the prior yr. AMD launched nearly 30 different graphics cards, with the large majority of them using the old GCN ane.0 or ii.0 architectures.

The silicon chip veteran took a shotgun approach to the scheduling of production releases, though. In June, only ane week separated the appearance of the GCN 2.0 powered Radeon R9 390X (essentially a single GPU R9 295X2, with a clock crash-land) and the brand-new Radeon R9 Fury X.

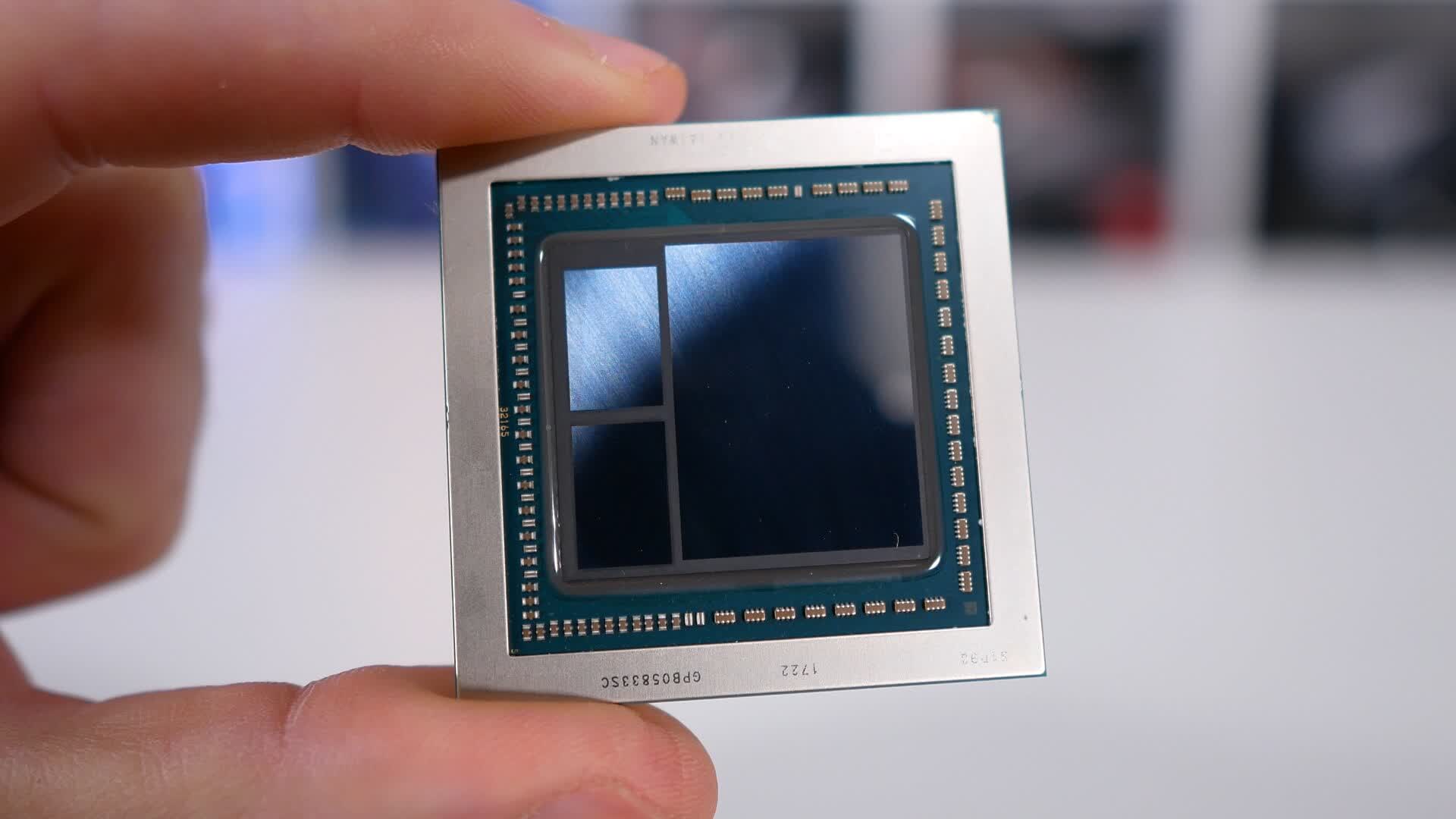

Although there was a $200 difference between the 2, the more expensive Fury could justify that price. The 596 mm2 GPU, codenamed Fiji, packed in an astonishing 4096 shader units -- 45% more the 390X. It was also the first consumer-level graphics card to use HBM (High Bandwidth Memory).

This applied science involves stacking the DRAM fries on height of each other and running the interconnects through them. The stop result being a far more compact system that provides lots of memory bandwidth, admitting with no more than than 4 GB of it in total, for the outset iteration.

But all those shaders and fancy new RAM came at a cost -- both literally and figuratively. The meridian power consumption was high (though no more so than the R9 390X) and AMD'south design had problems with temperature. Thus the Fury X was sold with an integrated water cooling setup, that turned out to be very effective.

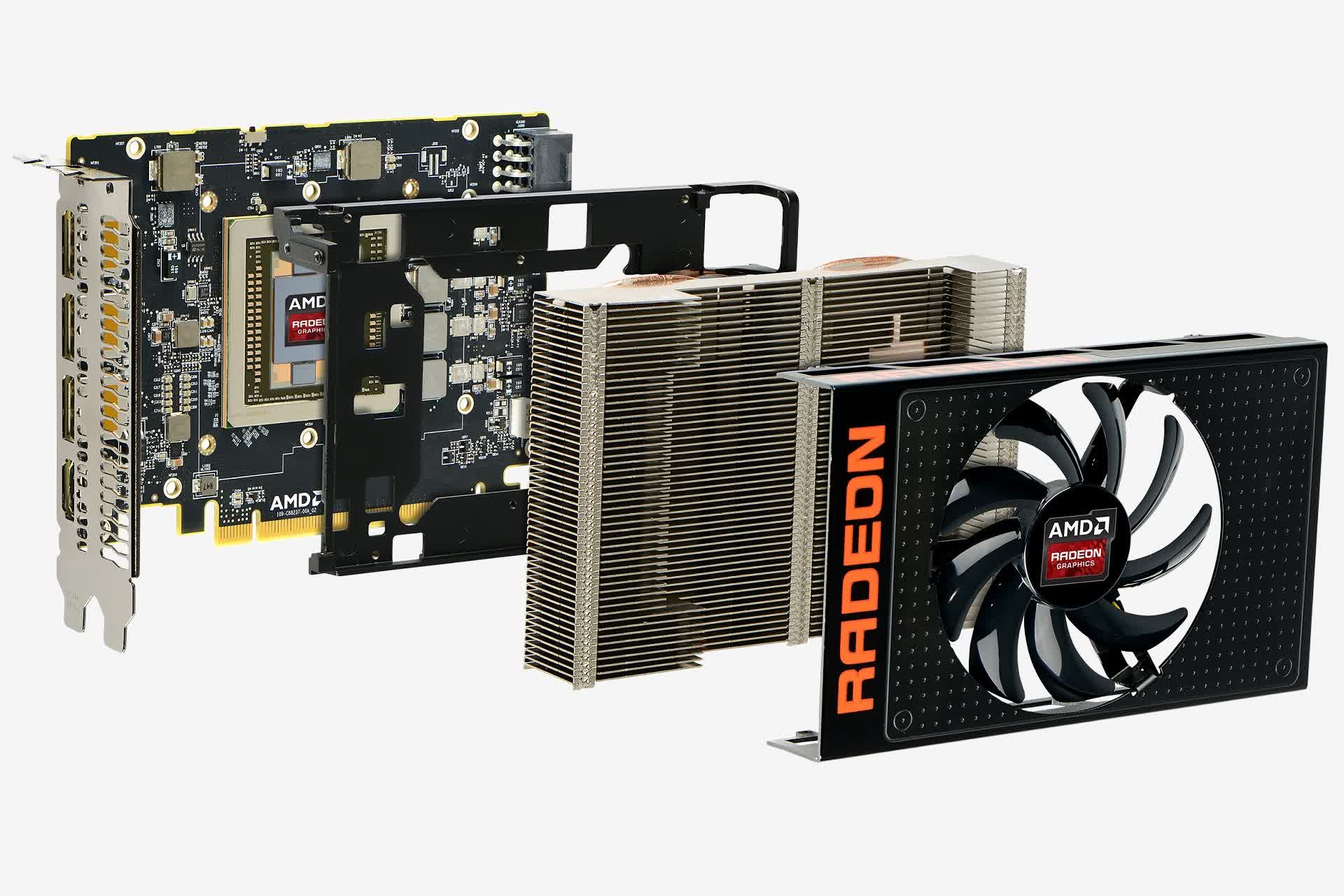

The not-X version ran only about cool enough to not require it, due to having lower clocks and viii Compute Units disabled, and all 3rd party variants of the model used traditional heatsink and fan combinations. As did the Radeon R9 Nano, AMD's babe version of the Fury 10, that came to market a month later.

The Republic of the fiji islands-line of graphics cards were AMD's best performing by a large margin and despite the price tag, heat, and comparatively small amount of memory, it sold extremely well. It would come to face up stiff competition from Nvidia, fifty-fifty though they generally had a relatively low-key showtime half to the year, with respect to heady new products.

Something else that AMD brought out in early on 2022 was FreeSync -- a royalty-complimentary alternative to Nvidia's proprietary One thousand-Sync (read our 2022 take). Both were variable refresh rate systems that allowed monitors to remain synchronized to frame updates, reducing the problem of screen tearing, without locking the rate of changes in identify.

Radeon GPUs had featured the power to do this for a while, whereas GeForce chips at the time required an external device to exist built into the monitor.

For Nvidia, the bulk of their releases were budget and mid-range models, with the most notable being the GeForce GTX 960, making an appearance at the showtime of the yr. At just $199 and using 120 Due west, information technology was a better demonstration of the progress Nvidia had made with the Maxwell architecture.

Performance-wise, information technology was on par with the likes of the Radeon R9 280 and 280X, and a fiddling cheaper. This was entirely down to the difference between the chips used in the competing products -- the GTX 960 housed a 228 mmii GPU, comprising ii.94 billion transistors, whereas AMD's older models used 432 mmii chips, with 4.31 billion transistors.

Despite both being manufactured on TSMC'south 28 nm process node, the newer architecture highlighted how much progress had been fabricated since GCN 1.0 first appeared.

At the other stop of the GPU calibration, Nvidia only offered two new models and both used the same GM200 chip. The GeForce GTX Titan Ten launched in March and the GeForce GTX 980 Ti in June. With a price tag of $999, the onetime was targeted at a very niche market, just the 980 Ti was launched at $649 -- still very expensive, only far more palatable to a wider audience.

The Radeon R9 Fury X had even so to appear, and Nvidia'southward elevation graphics cards were being pitched confronting the likes of the R9 295X2 and 290X. Depending on the game, they offered ameliorate functioning, although AMD's models were far more cost-effective.

2015 also saw software releases and announcements that would keep to shape the direction that GPUs and their vendors would follow for their forthcoming architectures. In March, at the annual Games Developers Conference, the Khronos Group publicly named the project they were working on: Vulkan became a hot topic.

This new graphics API was offering meaning benefits over OpenGL and Direct3D, mostly in the form of transferring a lot of the management of memory, threads, and the GPU itself to the developers and abroad from GPU drivers. This would help to greatly reduce the CPU overhead that the systems in place at the time were struggling with.

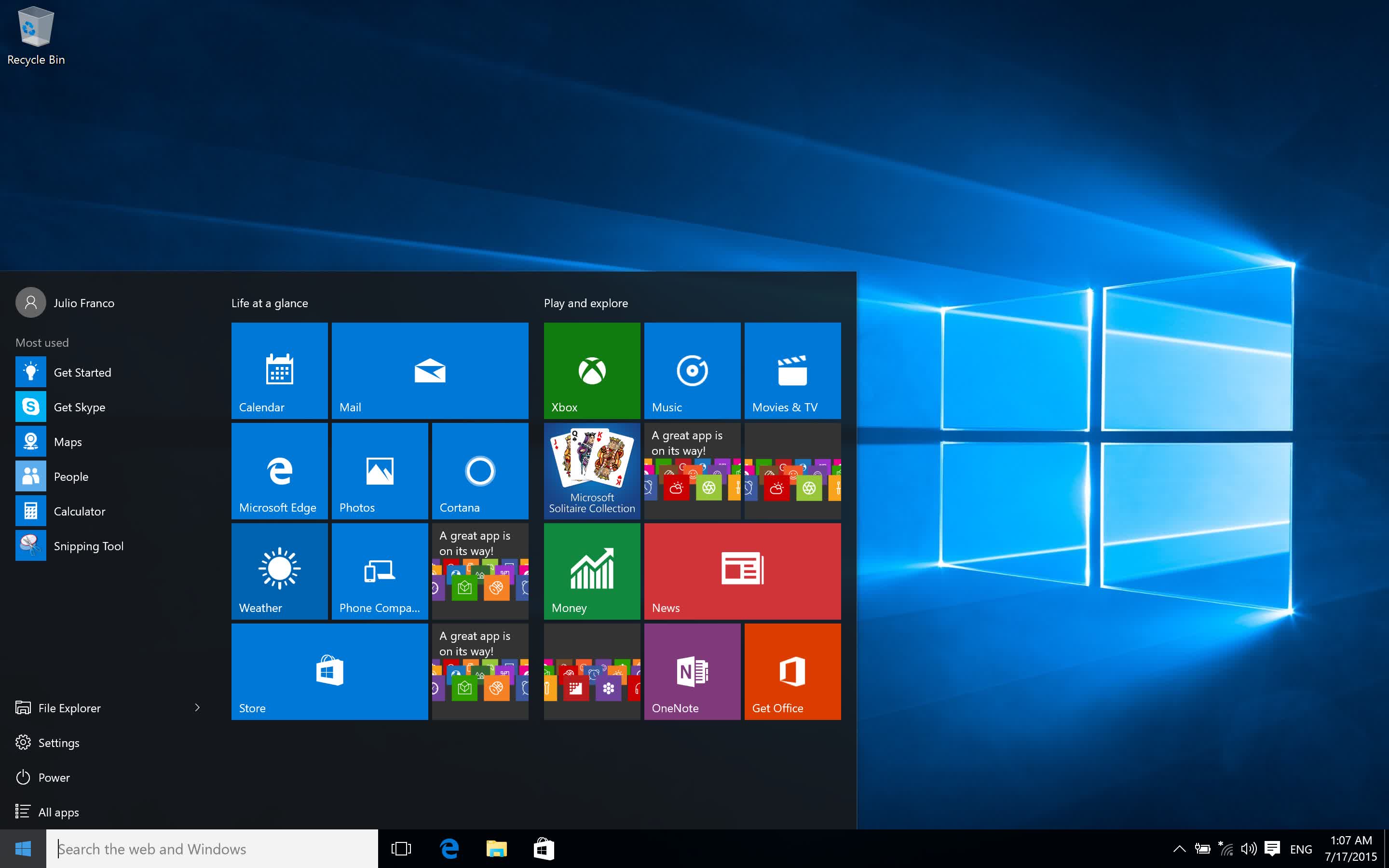

Four months later, Microsoft launched Windows 10 and along with information technology, DirectX 12.

The graphics portion of this API called Direct3D offered similar features as Vulkan, although information technology was restricted to the new operating system simply -- users with older versions of Windows were forced to remain with DirectX eleven.

Not that it had the best of promotional starts, though. The first DirectX 12-only game was, naturally, a Microsoft i -- Gears of State of war: Ultimate Edition. The title was a catastrophic mess, with numerous bugs and dire performance. Other games using the new API were to announced in the following year, merely it would take longer for the software to reach its full potential.

One of its features, asynchronous compute, was of particular interest to developers. Compute shaders had been a role of DirectX for a while, having first appeared in DX11 in 2008 (and via extensions in OpenGL and Nvidia's CUDA software). Handled specifically by the API DirectCompute, these shaders ran on a separate pipeline to the graphics i (east.g. vertex, geometry, pixel shaders) and leveraged greater general purpose computing ability to a GPU.

Switching betwixt the pipelines typically resulted in a performance penalty, and so the ability to execute both at the aforementioned fourth dimension with asynchronous compute, was potentially powerful. However, despite both AMD and Nvidia claiming their latest architectures were DirectX 12 compliant, merely AMD'south GPU made best employ of the feature -- Nvidia'south Maxwell chips weren't designed to operate in this manner especially well.

Before the yr airtight, Google shifted their TensorFlow software to open up source, giving the public full access to the library of artificial intelligence and machine learning tools. While it wasn't the first of its kind, Google's efforts that twelvemonth were matched by Intel (with DAAL), Microsoft (CNTK), and Apache (MXNet).

Graphics cards were already in use for such roles (AI, ML), but the increasing need for massively-parallel compute power would come to dominate how GPUs would exist adult.

Where Intel'south software was primarily for CPUs, Google and Apache'south were open to existence used on all kinds of hardware, and both AMD and Nvidia speedily integrated support for them with their own toolkits and drivers. Google themselves would go on to develop their own 'GPU', called a Tensor Processing Unit, to accelerate specific neural networks.

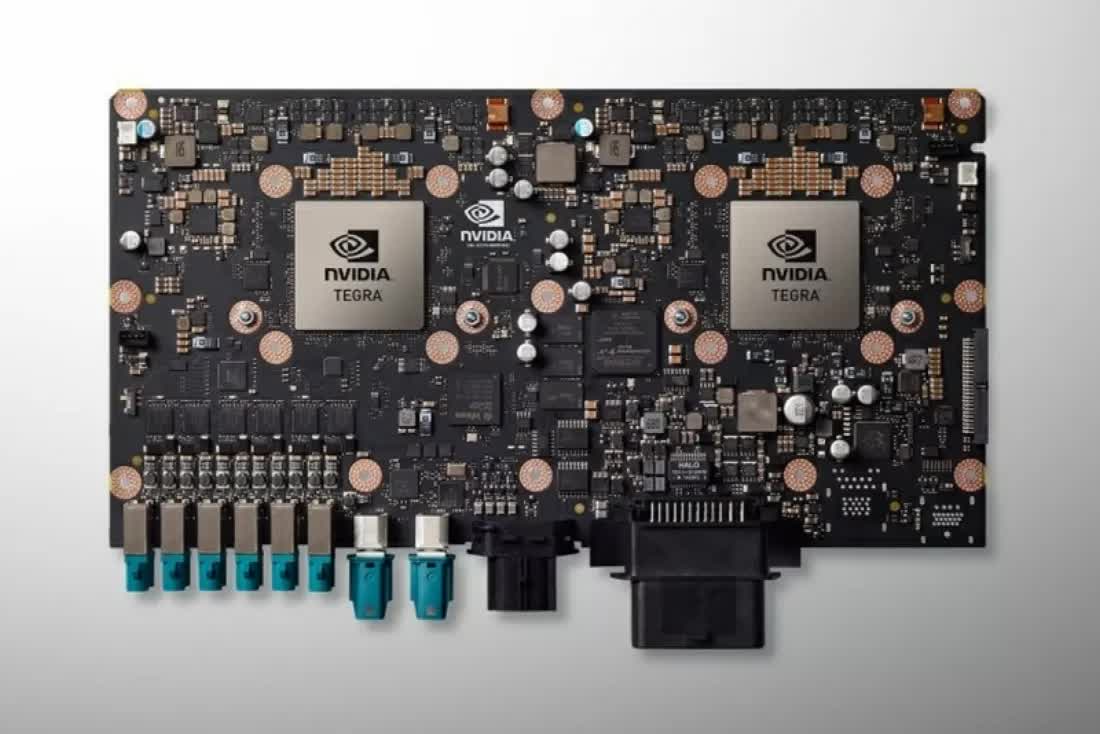

Graphics cards were already in use for such roles, merely the increasing demand for massively-parallel compute ability would come to dominate how GPUs would be developed. Nvidia's beginning serious foray into the world of car learning came in the form of the Jetson TX1 and Nvidia Drive.

Both systems used the Tegra X1 SoC. The modest bit contained CPU and GPU cores using the Arm Cortex-A57 compages for the sometime and Nvidia's own Maxell design for the latter. While information technology was no powerhouse, it marked a point in Nvidia's history that highlighted they were focused on doing more than just gaming.

A Golden Year for GPUs

Every PC enthusiast volition have a favorite slice of hardware, exist information technology for sentimental or financial reasons, and a skilful many of them will have originated in 2022.

AMD was still focused on tackling its banking concern residual and the largest portion of their inquiry and evolution budget was allocated to CPUs. Thus the graphics division, the Radeon Technologies Group, full-bodied improving profit margins through improved production yields and only relatively small architectural improvements.

GCN iv.0 appeared with the release of the Radeon RX 400 serial of cards in June -- the mid-range and upkeep models still housed GCN 1.0/two.0 chips, but the top-end RX 480 sported the new chip pattern. This GPU was significantly scaled back from the likes of Fiji, with just 36 Compute Units (CUs).

Every PC enthusiast volition have a favorite slice of hardware, be information technology for sentimental or financial reasons, and a good many of them will have originated in 2022.

Codenamed Polaris 10 (or Ellesmere), the graphics structure remained unchanged from GCN three.0, but had much improved display and video engines. But Polaris' key feature was its size: at just 232 mm2, it was sixty% smaller than Fiji. Part of the reason behind this came from the use of fewer CUs.

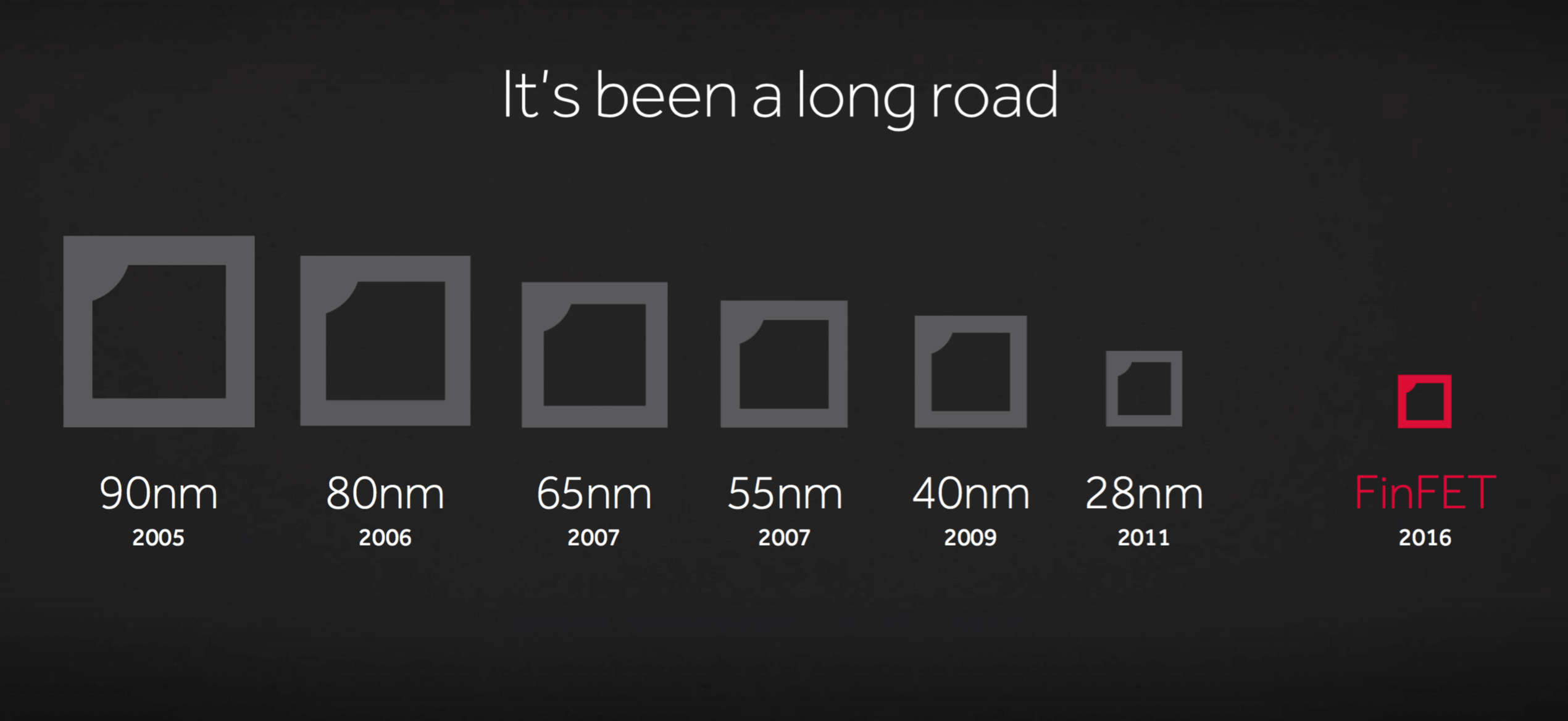

The main reason was the switch from using TSMC to GlobalFoundries for the manufacturing duties of the GPU. GloFo, as it's often called, formed in 2009 when AMD sold off its fabrication sectionalisation, and for the production of Polaris they licenced Samsung'southward 14LPP process node.

This system used FinFETs instead of planar transistors, every bit used by TSMC in their 28HP node that made Polaris' predecessors. The update allowed for higher clock speeds to exist accomplished, while reducing power consumption at the aforementioned fourth dimension, and offered much higher component densities.

The Radeon RX 480 wasn't designed to be the highest performing menu on the marketplace, just the nearly cost-effective 1, and at $240 it appeared to fit that criteria on paper. In reality, it was no better than the likes of the older Radeon R9 390 and GeForce GTX 970, and despite both those models launching at well-nigh $100 more, by this time they could purchased for the same cost.

For AMD, though, tiny size meant production yields would be far better than those accomplished with Fiji -- amend yields equals meliorate profit margins.

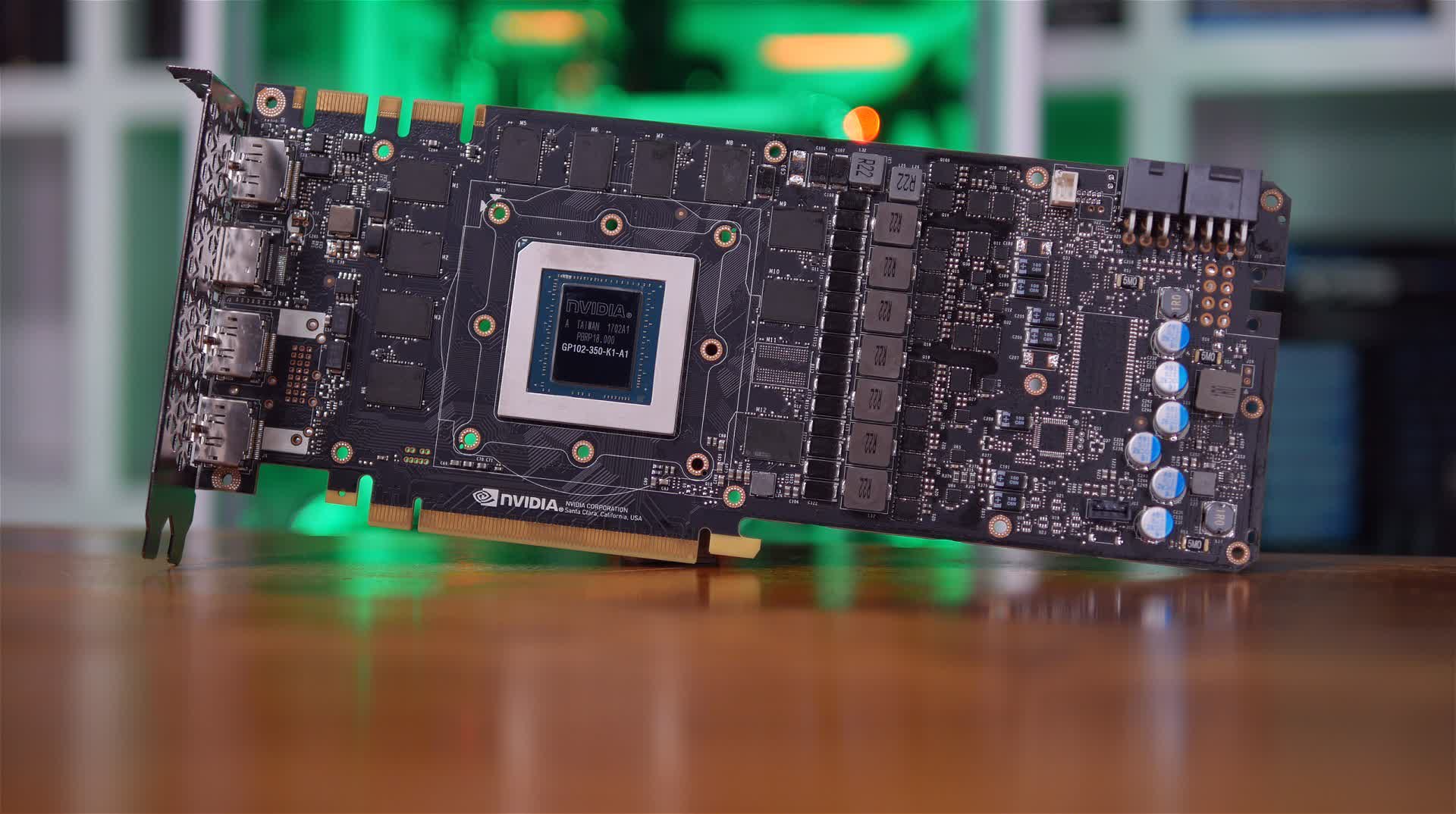

Nvidia remained with TSMC, using their new FinFET 16FF node for the manufacturing of their new architecture, Pascal. This first came to market in May 2022, in the form of the GeForce GTX 1080.

Nvidia's design too reaped the benefits of the new transistor technology, and while non as small as Polaris 10, the GP104 chip that powered the 1080 was 21% smaller than the GPU in the GTX 980.

Packed inside the GTX 1080 were 38% more transistors (7.two billion in total), clocked 42% higher, while consuming just 10% more than power than its predecessor. Information technology too sported a faster version of RAM, GDDR5X, giving it over twoscore% more memory bandwidth than the 980'southward GDDR5.

The MSRP was a steep $699, for the so-chosen 'Founders Edition' model, though 3rd party variants started at $100 less. But coming in at effectually sixty% faster, on boilerplate, than the GTX 980, and around thirty% faster than AMD's best (the Radeon R9 Fury X), the performance improvement ensured it sold very well.

Over the next six months, Nvidia would go on to release three new GPUs using the Pascal architecture: the GP102, 104, and 106. The latter 2 would power the likes of the GTX 1070, 1060, and 1050 -- all well received and popular purchases. The quondam would be used in Nvidia's nearly expensive single GPU desktop graphics bill of fare of its solar day.

The Titan Ten was launched with an asking price of $i,199 -- lxx+% more than expensive than the GTX 1080. That enormous figure was matched by the GPU's specifications: 3584 shader units giving upwardly to xi TFLOPS of FP32 throughput, 12 GB of GDDR5X RAM, and 384 GB/s of memory bandwidth.

Merely for all that ability, it wasn't 70% faster than the GTX 1080; many tests showed it to exist around 25% ameliorate on average. Not that it seemed to matter, as the Titan X sold just also as its lesser siblings.

The graphics menu market of 2022 offered something for almost every budget, from $100 through to $1,000. GPU performance and stability was notably better than it had ever been before, and game developers started to accept total advantage of their capabilities.

Nvidia was generating a healthy revenue and while its market place share decreased due to the popularity of AMD's RX 400 product line, overall shipments of discrete graphics cards were steadily dropping, due to the long running decline in global desktop PC sales.

More cores, more estrus... and more dollars

Past now, GPU vendors had fallen into a reasonably anticipated design: a new compages would be released every ii years or so, with lineup refreshes occurring in between, or sometimes both at the same fourth dimension.

For AMD in 2022, information technology was a case of the latter. The Radeon RX 480 was given a pocket-sized clock bump and rebadged as the RX 580 -- priced to undercut the GeForce GTX 1060 past $70, it performed a trivial faster overall, admitting with a higher power consumption.

The mid-range Radeon RX 560 was a notable improvement over the RX 460 it was based on: two extra Compute Units, more RAM, and higher clocks for a measly $99. Nvidia'due south GeForce GTX 1050, past now a year old, was slightly more power efficient and better performing, although the price tag was a fiddling higher.

It's worth noting that the GP107 powering the 1050 was manufactured by Samsung, using their 14nm node -- the same equally that used past GloFo to make the Polaris 21 GPU in the RX 560. Both had a TDP (thermal design power) rating of 75W, despite the Nvidia processor having more transistors and higher clock speeds.

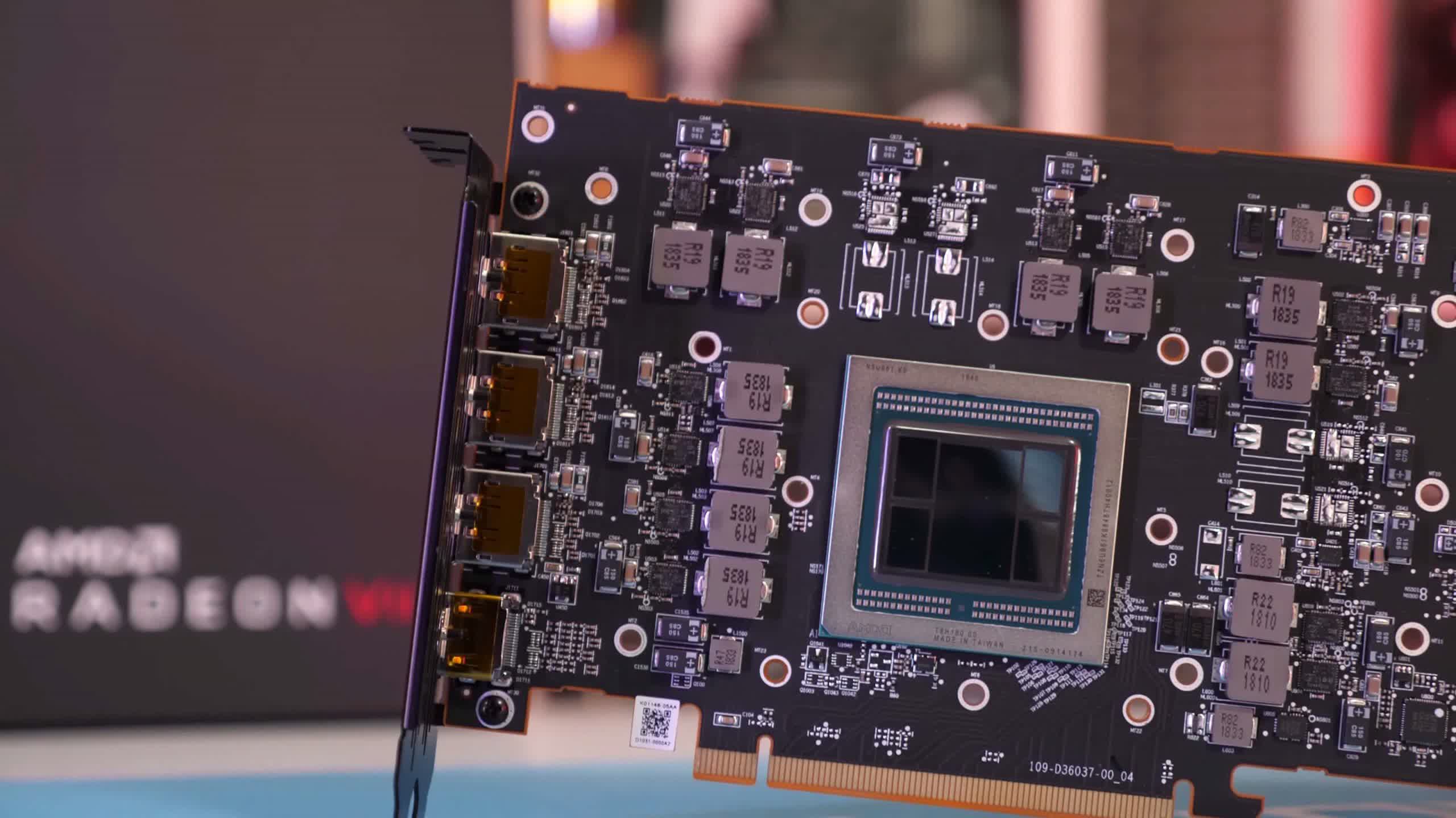

AMD'south relatively weaker control over ability was highlighted again with Radeon RX Vega cards, launched in mid-August. The Graphics Core Next compages was refreshed over again, to version 5.0, and the GPUs were substantially Fiji reborn. The top-terminate RX Vega 64 sported a 12.v billion transistor bit, 40% more Republic of the fiji islands, but due to the ameliorate process node, it came in at 495 mm2 to the latter's 596 mm2.

The smaller flake besides supported more than RAM, cheers to using new HBM2 technology, and the overall functioning was roughly the same as the GeForce GTX 1080. Despite its high power requirements (nearly 300W for some models), the standard version launched at $499 -- a total $100 less than the 1080.

Not that Nvidia were especially bothered. Their Pascal range of graphics cards were selling well, and in March they reinforced their agree over the enthusiast sector with the GeForce GTX 1080 Ti. This new graphics card used the same chip as establish in the Titan X, admitting with fewer shader units enabled.

But with higher clocks, it performed near the aforementioned as the halo model but sold for $500 less which seemed like an expensive bargain in comparison. The launch also saw the MSRP for the GTX 1080 drib by $100, and sales of both models ready new records for the Santa Clara firm.

Nvidia introduced a new architecture in 2022, merely non for the general consumer. Volta was aimed at the professional person compute marketplace, just its design and characteristic set would come to strongly influence the direction of futurity GeForce products.

Information technology was the first Nvidia scrap to characteristic an sectional architecture for a specific market place. All previous compute-focused products, such as the Tesla K80, were derived from structures constitute in consumer desktop and mobile chips. Volta wasn't entirely unlike to Pascal, but at 815 mm2 in size, with 21.1 billion transistors and 5120 shader units, it was the largest processor they'd ever turned out.

At the other end of the scale, GPUs integrated into CPUs or system-on-chips (SoCs) had made solid progress as well. Although Intel wasn't breaking whatever new applied science boundaries with their Coffee Lake CPUs, their graphics architecture had reached Gen 9.5 and, depending on the CPU model, upwardly to 48 EUs -- each one now vii threads wide, with up to four instructions co-issued per clock.

Naturally, gaming performance was still hampered by the overall scale of the GPU, and faired rather poorly confronting AMD's new Zen-based CPUs with integrated Vega GPUs. But it showed that Intel was still determined to improve the compages.

This became particularly clear when they announced that AMD's caput of the Radeon Grouping, Raja Koduri, had joined Intel with the specific goal of developing new discrete graphics products.

The final time Intel had offered a discrete graphics for the desktop PC marketplace was nearly two decades agone, and while integrated GPUs was 1 thing, it was entirely different thing to scale such designs into competitive products to fight AMD and Nvidia's offerings.

The world of smartphones also saw consequent progress with their graphics processors. Apple tree was successfully using their ain blueprint, and although elements of the arrangement used licenced engineering science from PowerVR, they appear that they would exist parting ways -- a motility that did irreparable damage to the fabless company.

For Android fans, Arm offered the likes of the Mali-T860 and Qualcomm had a perfectly respectable GPU in their Snapdragon 600 series of mobile SoCs. Even Nvidia's two-year-old Tegra X1 chip found a popular home in the Nintendo Switch.

This should accept been another 'aureate year' for GPUs. There were numerous models for every budget and sector, and AMD and Nvidia seemed reasonably well matched except at the very top of the graphics performance ladder.

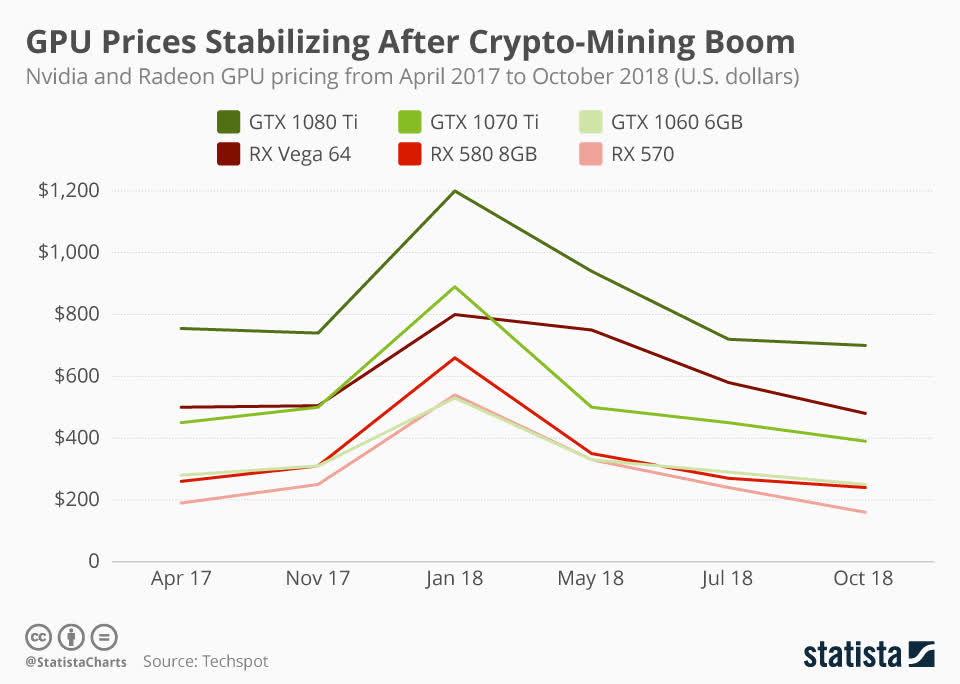

However, something that had been brewing in the groundwork, for a number of years, suddenly exploded and PC gamers and enthusiasts bore the brunt of the aftershock. The use of GPUs for cryptocurrency mining dramatically rose due to the meteoric ascension in the price of Bitcoin.

Supply of new GPUs ran dry out and prices of 2nd hand cards notably increased. GPU mining became a thing because the graphics processors were found to be extremely adept at doing lots of elementary mathematics en masse. AMD's GPUs were especially skillful at compute, although Nvidia'southward were more than power efficient.

Regardless of the difference, both mid-range and top-stop models saw consequent increases in price (likewise equally a continued dearth in availability), that ran well into the post-obit year. And if consumers were hoping that the products for 2022 would exist bring some sanity dorsum to their wallets, they were in for a bit of a daze.

New engineering, new marketing names, new prices

AMD enjoyed a successful launch of their fully redesigned Zen CPU architecture, later on which it took a cautious approach to spend limited resources (both financial and physical) on developing their GPUs. Rather than refreshing a bit's internal features or introducing an update to Vega, they stuck to familiar grounds: rebadging.

Thus, the Radeon RX 500 series remained as it was from the previous year, admitting with an 'X' tacked onto the model name -- for example, the RX 580 became the RX 580X, and and then on. Some of the mid-range and budget models were given a boost to the amount of RAM they sported, but other changes were scarce.

The only new product AMD brought to marketplace was the Radeon RX 590. It used the same GCN 4.0 Polaris fleck as the RX 580 and specs were almost the same, also. Yet, this chip was made by GlobalFoundries and Samsung, using improved process nodes (GloFo - 12LP, Samsung - 11 LPP).

The end result was a five% reduction in the TDP, a 17% college base clock, and a xv% higher boost clock -- and an extra $fifty on the MSRP, for good mensurate. Such small changes didn't make the RX 590 stand out in any way, and the 580 (now in the form of the 580X) fared much amend in stores.

Nvidia started 2022 in a similar fashion, bringing amended versions of their GTX 10 series to market, such as the miserable DDR4-equipped GeForce GT 1030. None brought anything new to the table, just it didn't matter so much in the first few months of the year, as GPU prices were so high.

By the summertime, matters had improved, and PC enthusiasts eagerly awaited Nvidia's new compages. The gap between new GeForce designs had been steadily increasing over the decade -- fifteen months separated Maxwell from Kepler, and in that location were 28 months between Pascal and Maxwell.

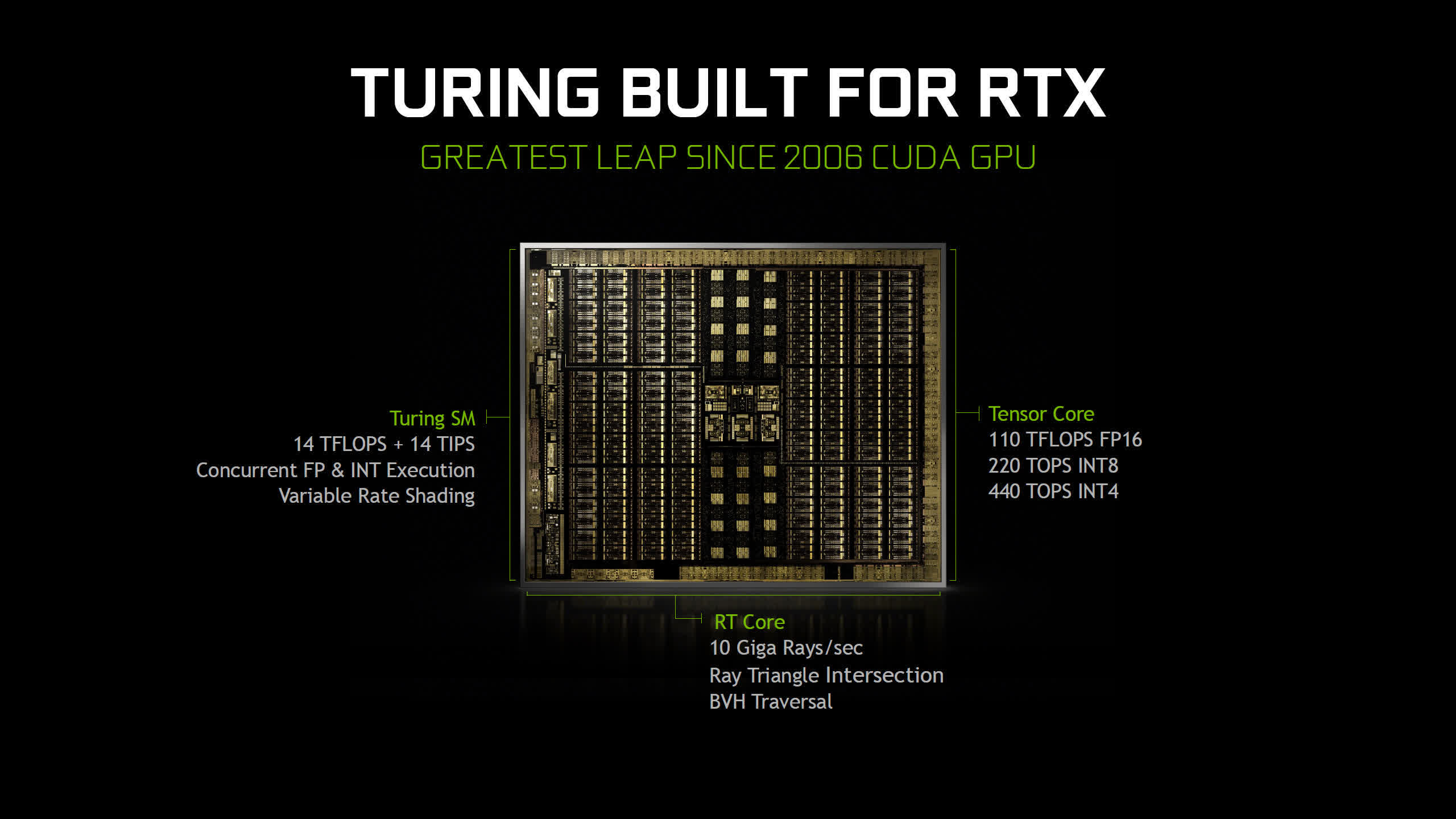

The first Turing GPUs appeared on shelves in August and September. The very first was a Quadro model for the professional workstation market. The GeForce lineup brought non simply new GPUs and cards to purchase, but new technology and marketing terms.

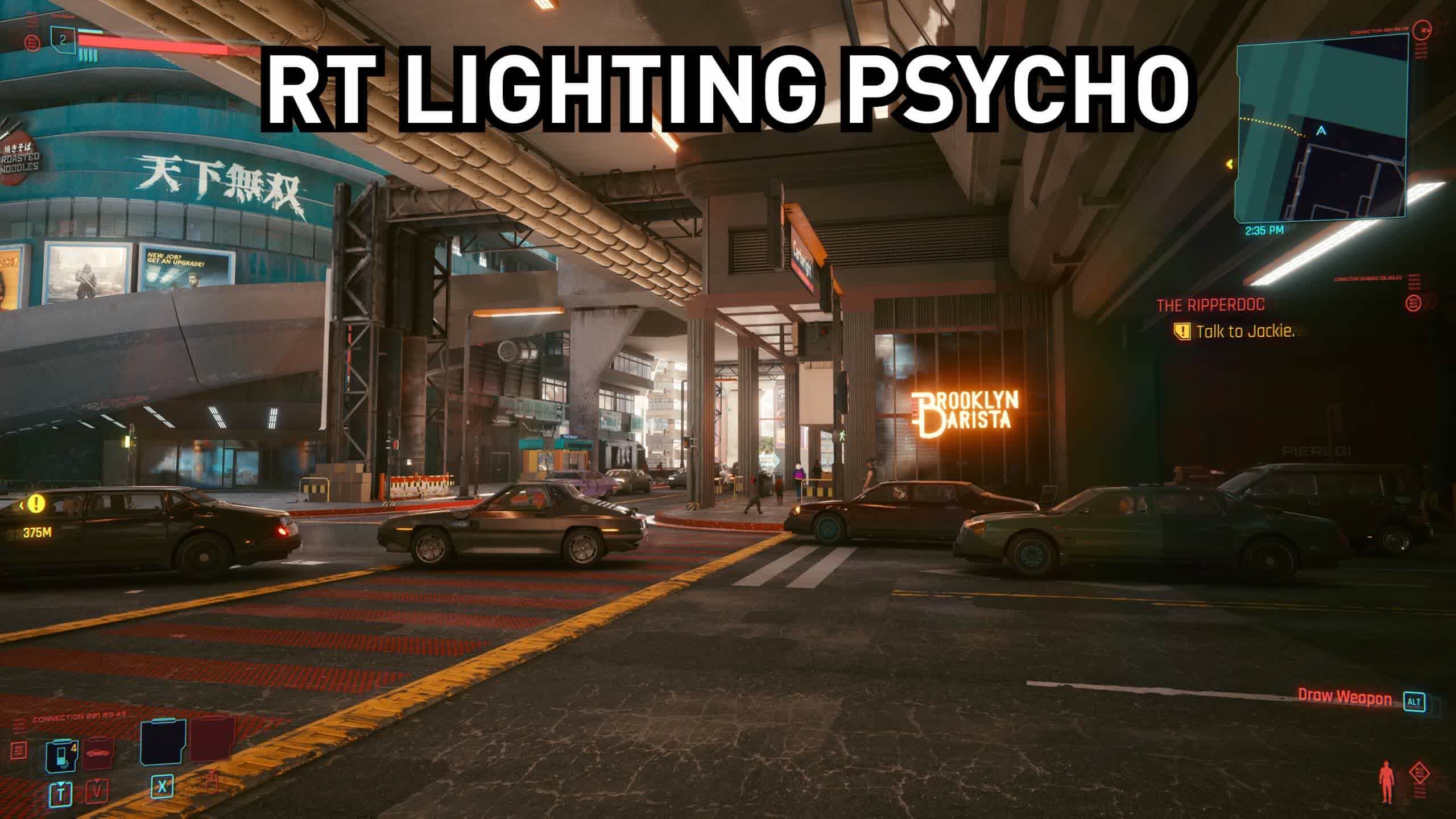

Nvidia had used the 'GTX' characterization as a prefix or suffix, since 2005 but now information technology was being replaced in favor of RTX, with the RT part finer standing for ray tracing. Once the preserve of the picture show industry, the ability to more accurately model real-time lighting was becoming available in a standard desktop graphics carte du jour.

Earlier on Microsoft had announced a new API, called DirectX Raytracing (DXR) at that year'due south GDC event. They detailed how the system worked, and showcased a number of videos from EA, Ballsy, and Futuremark. While Nvidia and the RTX moniker were also involved, it was via Volta GPUs, non Turing.

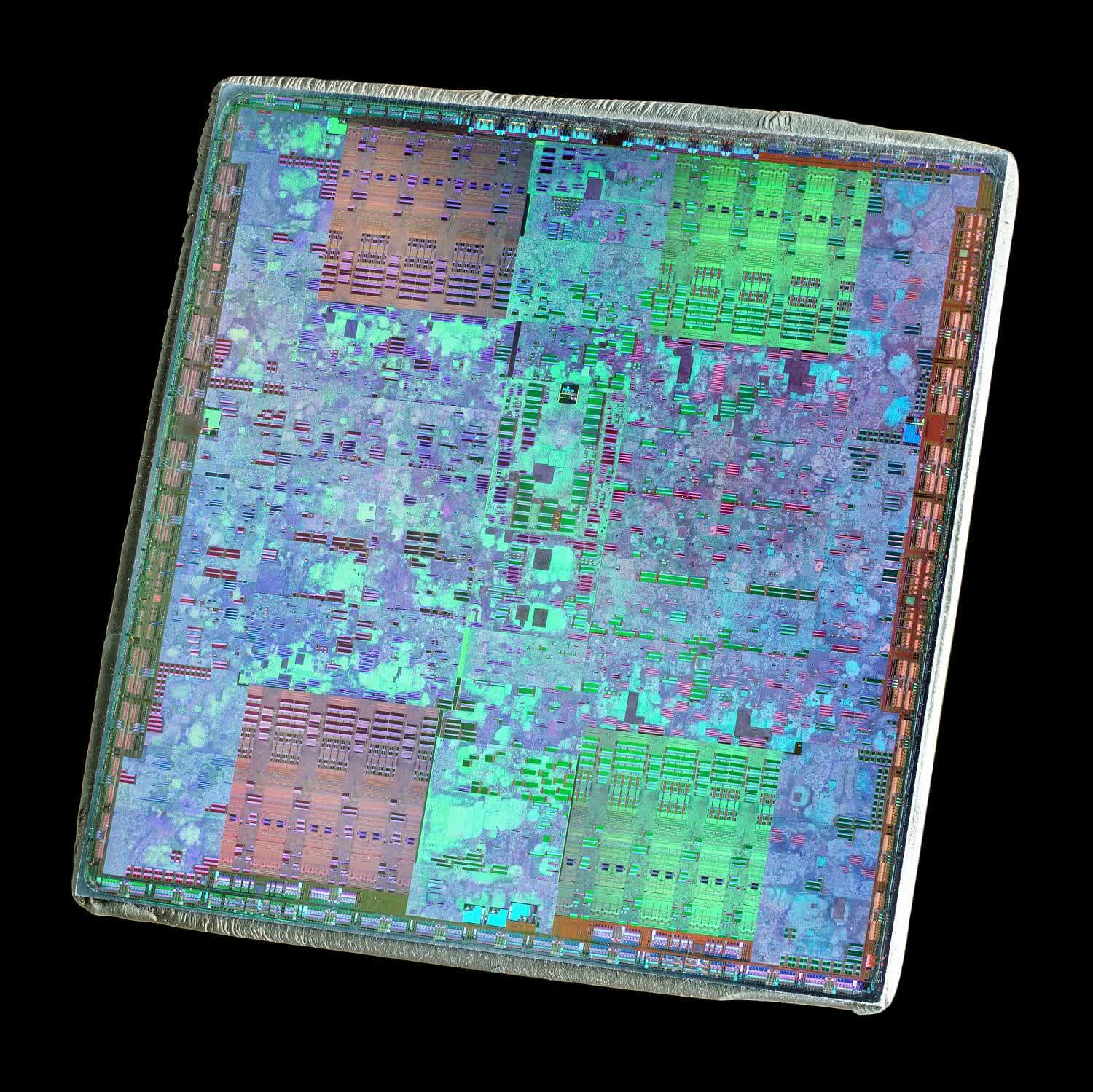

We got to see how this new compages handled ray tracing with the GeForce RTX 2080 and 2080 Ti, both of which used the same TU102 scrap. With 18.vi billion transistors and 754 mm2 in size, it made the Pascal-based GP102 expect tiny in comparison. Despite sporting merely over 4600 shader cores, it only had xx% more than its predecessor, so why was it so much larger?

Plenty of changes nether the hood accounted for the increase. L1 and L2 caches doubled in size, the internal bandwidth greatly improved, and the add-on of tensor and ray tracing cores to every SM (streaming multiprocessor) in the GPU all played their part.

The tensor cores -- essentially a collection of FP16 ALUs, then they handled FP16 shader code, too -- had surfaced in Volta, but had been updated slightly for Turing; the RT cores were completely new, with each 1 containing 2 specialized units: one for handling BVH traversal algorithms and the other for testing ray-primitive intersections.

Techno-babble aside, such circuitry isn't absolutely necessary, equally ray tracing could be (and was) done on CPUs. But for doing it in existent-fourth dimension, in everyday games that anyone could purchase, and then such hardware was categorically required.

However, with no titles available for testing, offering DXR support or its equivalent via OpenGL/Vulkan extensions, when the new Turing chips appeared, reviewers turned to its raw functioning in 'normal' games. The results, for the Ti version at to the lowest degree, were suitably impressive and further cemented Nvidia's hold over the top-end crown.

What was far less impressive, though, were the launch MSRPs -- for the GeForce RTX 2080 Ti, Nvidia had set up the tag at $999, and $699 for the 2080 (and $100 actress for Founders Editions).

In the example of the former, that was a full $300 more the GTX 1080 Ti, although the RTX 2080 was a more than palatable $100 increment over the 1080. Merely with GPU values simply just returning to normal after the crypto mining debacle, a 43% increment in the price tag for the Ti was felt past many to exist unjustified.

With the Turing line still being made by TSMC, albeit on a customized version of their 16FF procedure node (labelled 12FFN), the enormous fries would never generate the same level of yields that the 38% smaller Pascal GP102 dies could achieve. AMD had experienced a similar problem with the likes of Republic of the fiji islands and Vega, although they more than willing to absorb the higher production costs.

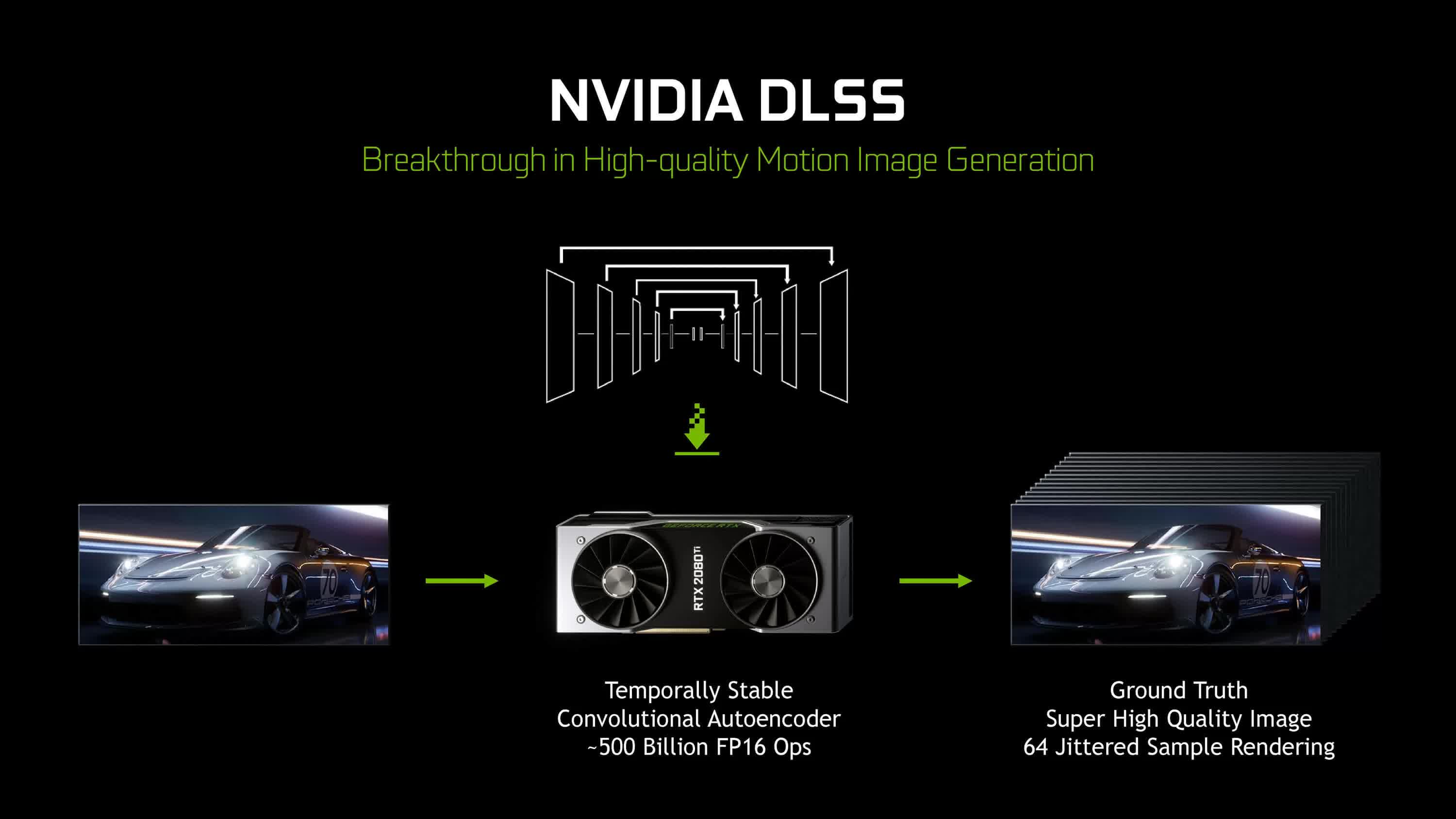

Another element of new GeForce RTX cards was much-touted by Nvidia: DLSS or Deep Learning Super Sampling. The general idea backside DLSS is to return everything at a lower resolution, and so apply an algorithm determined by machine learning to upscale the final frame to the monitor's resolution.

The tensor cores were promoted equally existence a primal element backside this feature, simply the start version of DLSS didn't utilise them in the consumer's graphics cards. Instead, this was all done by Nvidia's own calculator grids, which were used to clarify each game, frame past frame, to work out what the upscaling routine would be.

Initial impressions were positive, as the lower resolution rendering improved operation, while the upscaling was good enough to maintain decent image quality. But as with ray tracing, there were no total games using the technology for the launch of Turing.

A swansong, a new kickoff, and a alter of heart

For hardware reviewers, the end of 2022 and the early on months of 2022 gave them a amend opportunity to examine Nvidia'southward RTX feature set. By then, there were several titles bachelor that supported DXR and DLSS.

The likes of Battleground V, Shadow of the Tomb Raider, and Metro Exodus all used the systems, to varying degrees, but two things quickly became obvious: the apply of ray tracing had the potential to significantly improve the realism of global lighting, shadows, and reflections. And 2nd, the performance cost was uncommonly loftier, and only the use of DLSS helped maintain any semblance of playability. And this was at 1080p -- resolutions higher than this were merely non an option.

While frame rates of xxx fps or below were frequently the norm for consoles, when running games with extreme graphics, information technology was the antithesis of what PC enthusiasts had come to expect when shelling out $one,000 for a graphics card.

Effectually this time, both AMD and Nvidia released new graphics cards -- the onetime gave us the Radeon Vii, whereas the latter offered the GeForce RTX 2060 and the render of the GTX moniker, with the 1660 Ti.

The Radeon VII would be GCN's swansong: the final version of that long-running architecture, or so it would seem, before AMD switched to something new. The bit powering the bill of fare was the Vega 20, a version of that constitute in the Radeon Vega 64, admitting with a few tweaks, and manufactured on TSMC's new 7N node.

On newspaper, the model had everything going for it: sixteen GB of HBM2, sporting 1024 GB/s of bandwidth, along with 60 Compute Units running at up to one,800 MHz.

With an asking cost of $700, AMD was pitching information technology confronting Nvidia's GeForce RTX 2080 and on average, it was only a few percent slower in testing. But the production was never intended for gamers, as information technology was merely a rebadged Radeon Instinct, a workstation-level compute model.

The TU116-powered GeForce GTX 1660 Ti, on the other hand, was admittedly targeted at gaming -- especially for those with a clear heed on upkeep. For $279, y'all could say goodbye to Tensor and RT Cores and hello to a product to that was on-par with the $100 more expensive Pascal GTX 1070.

The GeForce RTX 2060 released at the kickoff of 2022, retaining all RTX features, information technology was well-nigh 30% more expensive than the GTX 1660 Ti, but only 12% faster on average, so it didn't offering the same value for money.

Both mainstream models offered some relief confronting Nvidia'south pricing of their enthusiast-level RTX models though -- in the case of the 2080 Ti, information technology had risen by over $300. Later they would be joined by the likes of the GTX 1650, released at $149.

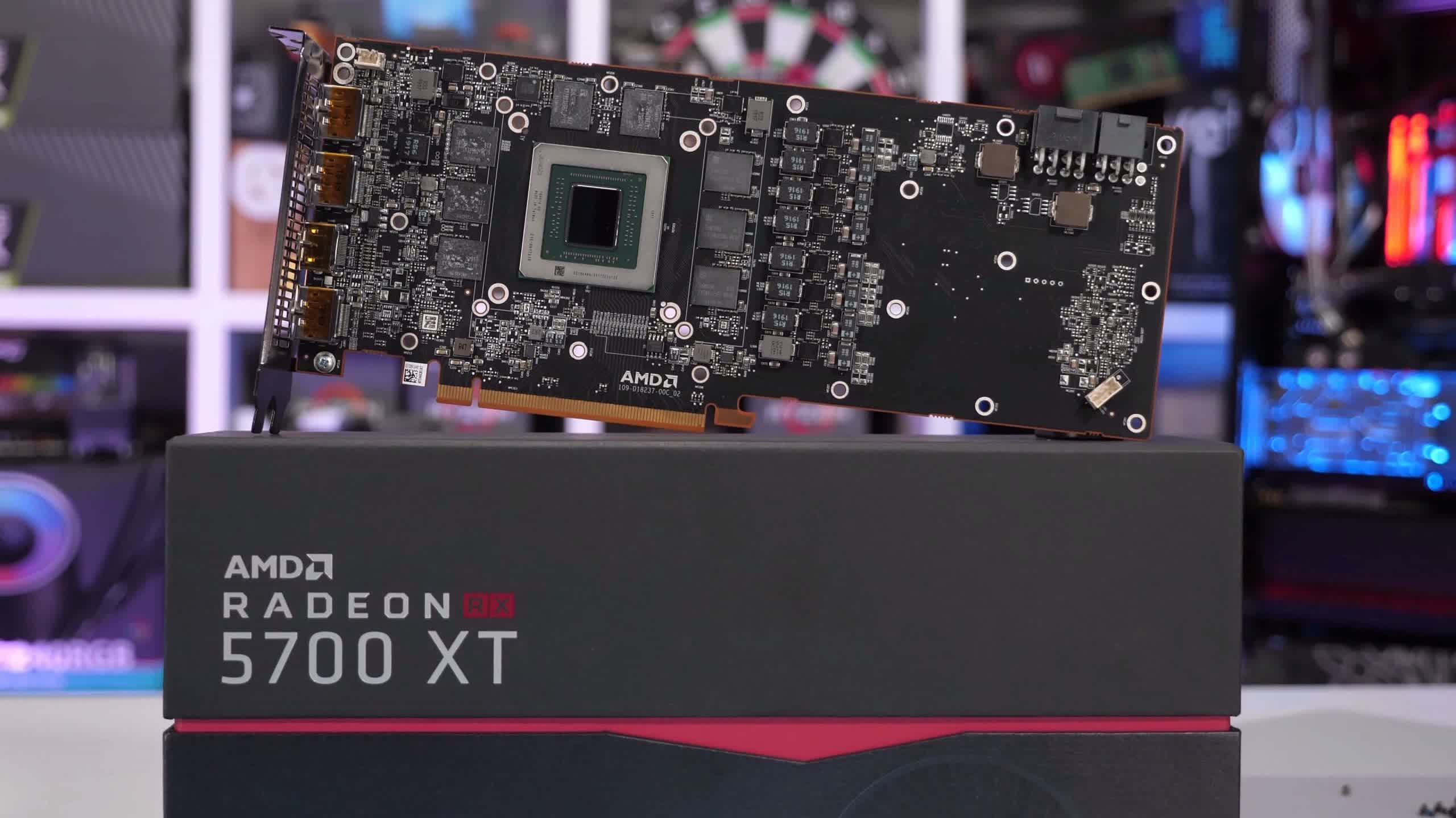

AMD held their new architecture hidden away until the summer, when they released the Radeon RX 5000 series, powered past Navi 10 chips. The GCN architecture had been given a thorough overhaul, transforming into RDNA, and with information technology addressing many of the limitations that the older blueprint suffered from.

Where Nvidia was aiming to please all markets with Turing, casual and professionals alike, RNDA was all nearly games. The basic specs pointed to it existence worse than the Radeon Vega 64, with significantly fewer Compute Units. But AMD reworked the compages to improve instruction issuing and internal data flow, and the end consequence was a graphics card that wasn't that far behind a Radeon VII and GeForce RTX 2070. Launching at $399, information technology undercut both models, and with the chip existence a svelte 251 mm2 in size (due to TSMC's 7N node), it gave AMD good yields too.

While some people were disappointed that the new GPU wasn't a top-finish model, and criticisms over stability and drivers would somewhen go newsworthy, Navi proved that it was possible to have decent gaming performance without the need for enormous chips and toll tags.

Nvidia had readied a response to the Radeon RX 5000 family in the form of 'Super' models -- over the grade of 2022, the RTX 2080, 2070, 2060, GTX 1660, and 1650 would all exist refreshed with GPUs sporting more shader cores and higher clock speeds. The extra functioning was welcome every bit was the fact that the MSRPs hadn't changed, bar the 2060'due south.

Intel's detached GPU projection was starting to accept shape. By now information technology had a clear proper name, Xe, and some details about potential models were being discovered. Its commencement outing though, would nonetheless exist in the integrated graphics market.

An end of a decade -- new chips, new threats, worse problems

2020 would plow out to exist a year of disparate fortunes. Against the background of a global pandemic, AMD, Intel, and Nvidia all released new graphics cards containing new architectures and production designs.

Microsoft and Sony too brought fresh consoles to market place, sporting a raft of new technologies and features, with the onetime consolidating several years of API updates with the release of DirectX Ultimate.

The professional globe of compute and AI were given the likes of the AMD Radeon Instinct MI100 and Nvidia A100, both featuring gargantuan GPUs (750 and 856 mmtwo respectively) with enormous ability (120 CUs giving 23 FP32 TFLOPs or 432 Tensor Cores producing 312 BF16 TFLOPs).

The former fielded AMD'south new CDNA compages, GCN reborn into a compute-only marketplace, whereas Nvidia used the new Ampere design. Information technology was marketed as a straight replacement for Volta, offer big performance increases for AI workloads.

Speaking of AI, Nvidia introduced an improved version of DLSS in March, which used a very different process to the first iteration. At present, the tensor cores in users' graphics cards would process the inference algorithm to upscale the paradigm, and overall, the new organization was well received.

Desktop PC enthusiasts would take to wait to later in the year for a new batch of GPUs, only their patience was rewarded by the GeForce RTX 3000 and Radeon RX 6000 series of cards. Nvidia'due south models brought Ampere to the masses, although there were pregnant differences betwixt the GA100 scrap in the A100 and the GA102 that drove the RTX line-up. The latter was essentially an update of Turing, featuring improvements to the CUDA, Tensor, and RT cores.

In the instance of the general shader units, the integer ALUs could at present handle the same FP32 routines as the FP ones, and Nvidia utilized this to promote the 3000 series having double the number of cores as their predecessors. While not entirely true, it did mean that the GA102 had the potential to offer substantial floating point throughput.

Merely as games are not entirely limited past their FP32 shaders, the overall performance of the RTX 3090, 3080, and 3070 was less than the paper specifications suggested, though nonetheless a sizeable improvement over Turing. Meliorate yet, launch prices were mostly lower than those for the RTX 2000 range.

AMD took RDNA and tweaked critical aspects of information technology, such as power consumption, operating frequencies, and information throughput, to mitigate the factors that ultimately express the capabilities of the RX 5000 cards. RDNA 2 showed that the consequent progress made with the Zen compages was going to a visitor-broad goal.

Popularly known every bit 'Big Navi', the Navi 21 GPU housed twice the number of Compute Units than its predecessor, a substantial 128 MB of L3 cache, and adapted texture processors that would handle the ray-triangle intersection checks in ray tracing.

The Radeon RX 6000 serial would put AMD on a level playing field with Nvidia in well-nigh games, although the cards were notably worse when ray tracing was involved, and offered nothing like DLSS to boost performance.

The same RDNA two architecture, albeit with far fewer CUs and no extra cache, would ability the new Xbox and PlayStation consoles. Coupled with Zen ii processors on the same die, the updated systems left gamers salivating at the potential the devices had to offer.

Even Intel finally released a new discrete GPU, though only to OEM and system builders. Previously known equally DG1, the Iris Xe desktop card was nil to become excited about, but it highlighted that Intel were serious about competing in the graphics market.

All of the excitement and enthusiasm about the new releases would eventually turn to frustration and acrimony, every bit the usual problems of supply and exaggerated prices grew to farcical proportions. For desktop Ampere, Nvidia chose to use Samsung for fabrication duties and while never directly confirmed, the general impression, felt by many industry, was that their yields simply weren't as good every bit TSMCs.

Not that information technology ultimately mattered. As 2022 drew to a shut and the new decade started in earnest, the need for electronics and computing devices skyrocketed, due to millions of people effectually the world being forced to work from home. Equally the effects of Covid grew more serious, the production of basic components, such as voltage regulators and microcontrollers, became increasingly limited.

Supplies of GeForce and Radeon graphics cards turned uncommonly sparse, a affair non helped by another outburst in crypto mining and the pervasive apply of bots to mass purchase cards and consoles from websites. Almost every available GPU model significantly rose in price and second mitt prices matched or exceeded their original launch values.

And where the general consumer struggled with the dearth of options, AMD and Nvidia both enjoyed significant increases in the revenues, with the latter experiencing nearly a 30% growth in their gaming sector. Such figures would offer scant comfort for PC gaming enthusiasts, many of which were unable or unwilling to pay the extortionate prices that graphics cards were now demanding.

What does the future hold?

And and then, as we bring the 5th part of our history of the modern graphics processor to a shut, it would remiss of u.s. to not look ahead and come across if information technology's possible to make up one's mind what the next decade holds. The electric current situation, pertaining to supplies and prices, will not last forever, but information technology shows no signs of improvement in the firsthand future.

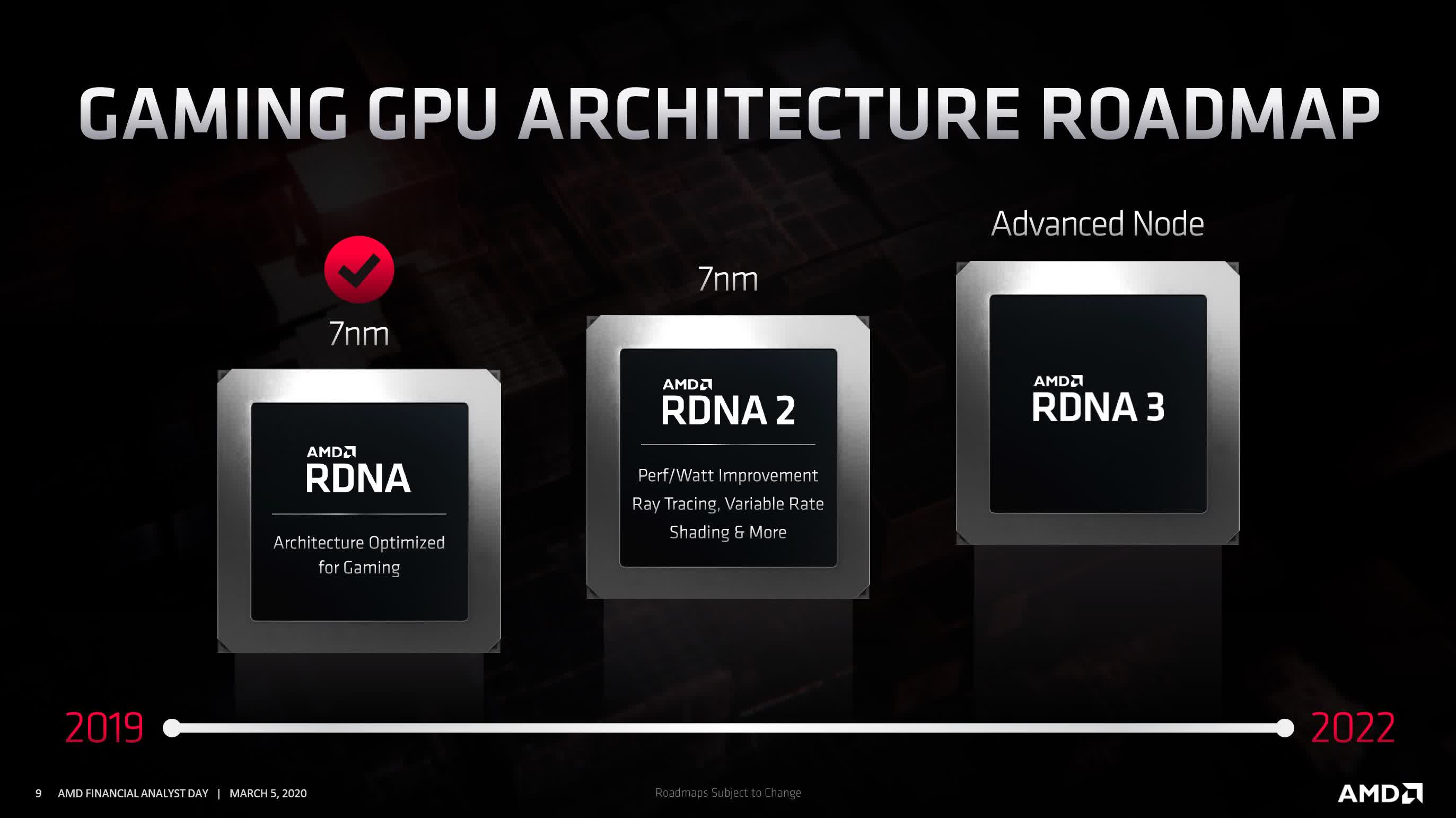

What we do know is that AMD had previously targeted 2022 as the year to release updates for the gaming and compute architectures: RNDA three and CDNA 2. Whether this holds truthful or non, given other circumstances, it'southward hard to predict but it's unlikely it will accept much longer that that.

Fundamentally, RDNA 2 is a refined version of its forebearer, with performance gains coming from a mixture of blueprint changes to improve clock speeds, pipeline efficiency, and reduced data motion. The but new feature are ray accelerator units, integrated into the texture processors.

We certainly won't meet a new major version of DirectX in 2022, so RDNA 3 is likely to be more of the same optimizations and tweaks. The above image states that it will also be manufactured on an 'Advanced Node' just this tells united states of america very piddling. Will they use TSMC's EUV-based N7+ node, or another one, such as N6 or N5?

The Navi 21 GPU used for the Radeon RX 6800 series is one of AMD'south largest chips ever designed for the desktop PC market, at 520 mm2 (but Republic of the fiji islands was larger). But as this is still 30% smaller than Nvidia'south TU102, it would suggest that there's telescopic for an even larger processor to striking shelves.

Nvidia is considerably more than reticent to publicly event roadmaps, and footling is known about what's next for them, other than rumors of it existence called Hopper (named after Grace Hopper, a pioneer in estimator science). Like RDNA ii, Ampere was an optimization of Turing, and having settled on a GPU structure that's inverse relatively little over the year, there'south a strong chance that information technology volition be more of the aforementioned.

And like AMD'due south Navi blueprint, there's telescopic for the next round of Nvidia GPUs to sport even more than shader units, cache, so on -- fifty-fifty if they retain Samsung for manufacturing duties, and don't even alter the node, the likes of the GA102 can be made 20% larger earlier it hits the aforementioned size as the largest Turing processor.

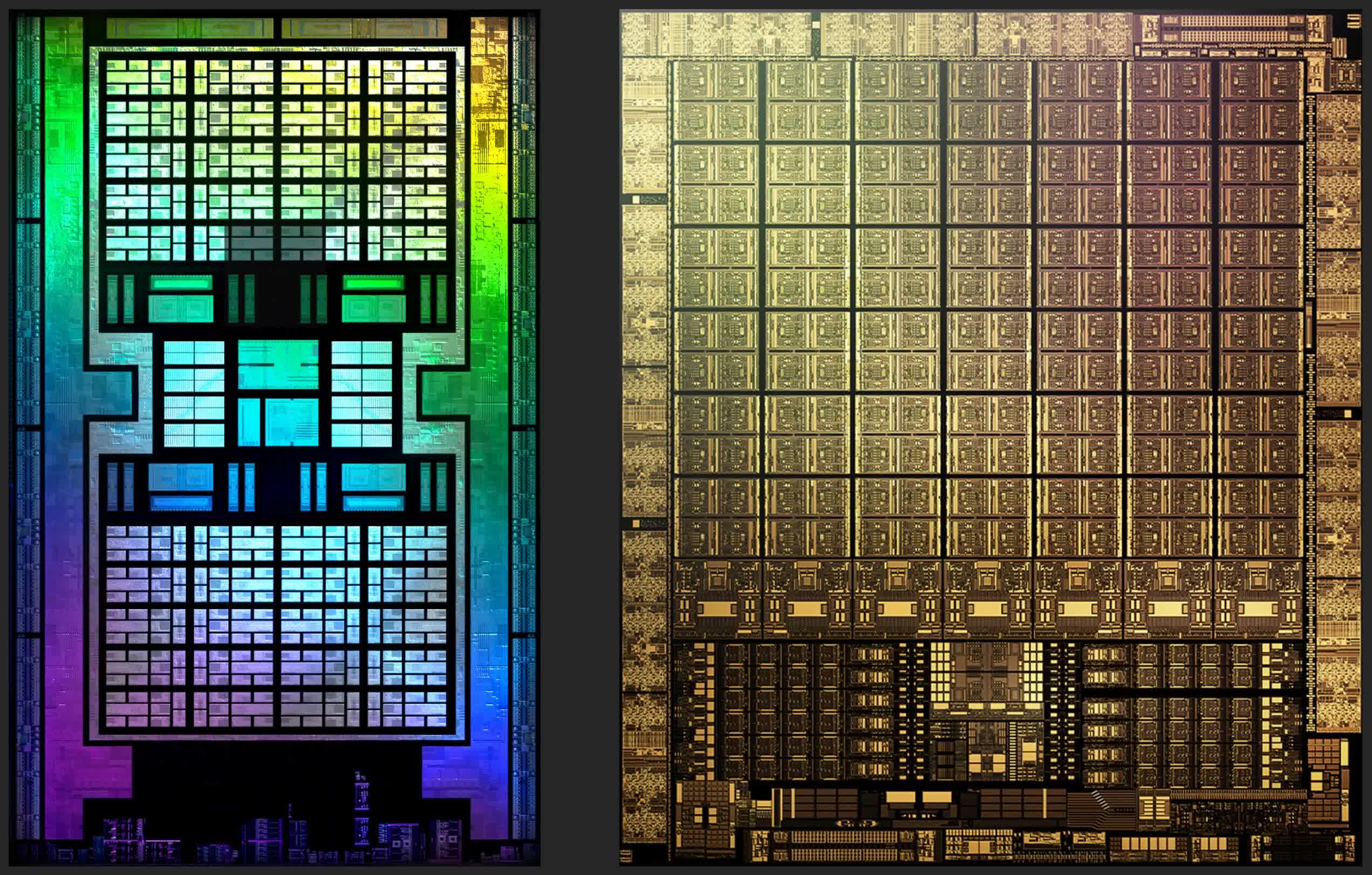

If nosotros ignore GPUs like Volta, which weren't intended for the consumer market, the TU102 was the largest single GPU to exist manufactured and sold for desktop PCs. At 754 mm2, it greatly restricted the number of dies that could exist extracted from a single 300 mm wafer -- around 80 or so, at best. And so could we see fries that size again?

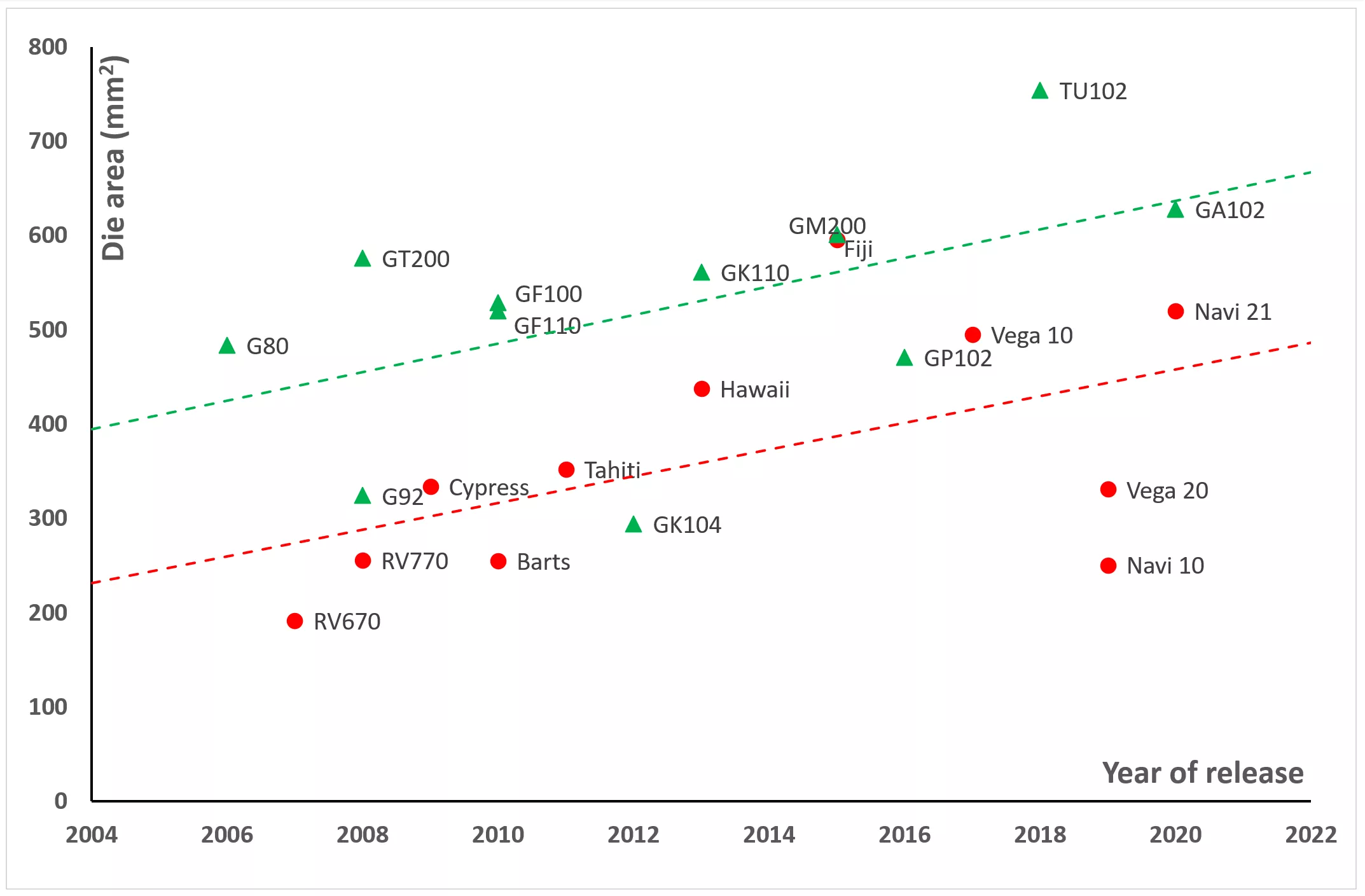

Taking a sample of AMD and Nvidia's largest GPUs over the years shows a vaguely linear trend in the growth of die sizes, but it as well highlights how altering the procedure node can brand an enormous difference (for instance, compare Vega 10 and 20 sizes). Withal, at that place'due south far too much variation in the data for it to be used to reliably estimate what size of processor one could be seeing over the next ten years.

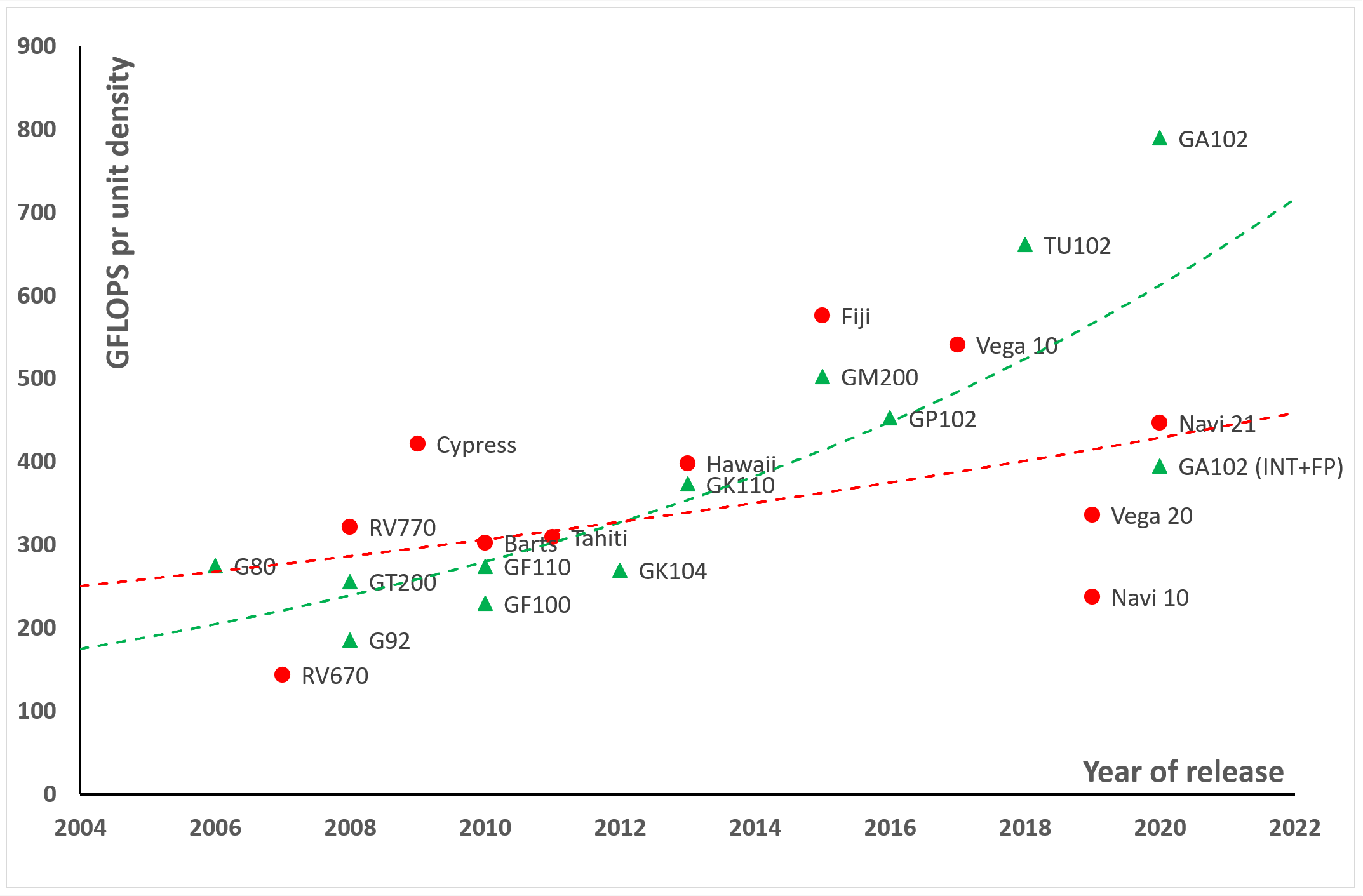

Perhaps a amend approach would exist to await at the processing power the above GPUs offered, for the given unit density (i.e. millions of transistors per square millimetre). While peak FP32 throughput, measured in billions of floating point operations per 2d, isn't the only metric that should be used to gauge the capability of a GPU, it is a comparable one. This is considering general shader operations form the bulk of the processing load and volition go on to do and so for a while.

When we await at a graph of those figures (below), information technology paints a rather different picture. In that location are outliers that bear on the trends somewhat, but even with them removed, the overall pattern is broadly the same.

It shows us that Nvidia has consistently focused on increasing raw processing power with each new design -- something that makes sense given how the aforementioned fries are used in general and professional person models. The same was true of AMD until they released RDNA, where the product is solely aimed at gaming.

GCN lives on in the form of CDNA and likewise in integrated GPUs in Ryzen APUs, and although in that location is just one GPU using that compages, it would actually place lower than Navi 21 does on the chart. This is because that design is targeted for AI workloads, where standard FP32 processing is less important than integer and tensor workloads.

With both Nvidia and AMD offering ray tracing acceleration, too equally support for data formats and math operations needed for machine learning in their latest GPUs, PC and console games of this decade are increasingly going to utilize them. Just as anti-aliasing and tessellation were once too demanding and could but be used sparingly, the aforementioned will be truthful of today's performance hogs.

Does this mean that GPUs of 2030 will exist routinely hitting 800 mm2 in size and produce well over ane TFLOP per unit density? Will they increasingly favor ray tracing and machine learning over traditional aspects such as full general purpose shaders or texture processing? Possibly, but there's a critical aspect to all of this that may curtail such growth patterns or changes in primal GPU design, and it all revolves effectually data motility.

Having thousands of shader units, tensor or ray tracing cores is all well and practiced, but they'd exist left hung out to dry if they couldn't fetch or write information fast enough. This is why enshroud size and internal bandwidth has grown then much, always since the start of the GPGPU industry.

The Nvidia G80, the visitor's offset fleck to use unified shaders, sported but xvi kB of shared memory for each SM (streaming multiprocessor), sixteen kB of texture cache for a pair of SMs, and a total of 96 kB of Level 2. Compare that to the GA102, where each SM gets 128 kB of L1 cache and the whole GPU contains 6144 kB of L2.

As process nodes develop and component features reduce in size, it would seem that fifty-fifty more than can exist packed in. However, SRAM (the principal building cake of cache) scales downwards far worse than logic systems do, and with so much of a modern graphics processor existence cache, chip sizes may well balloon in size without increasing the shader count or ray tracing ability by the same scale.

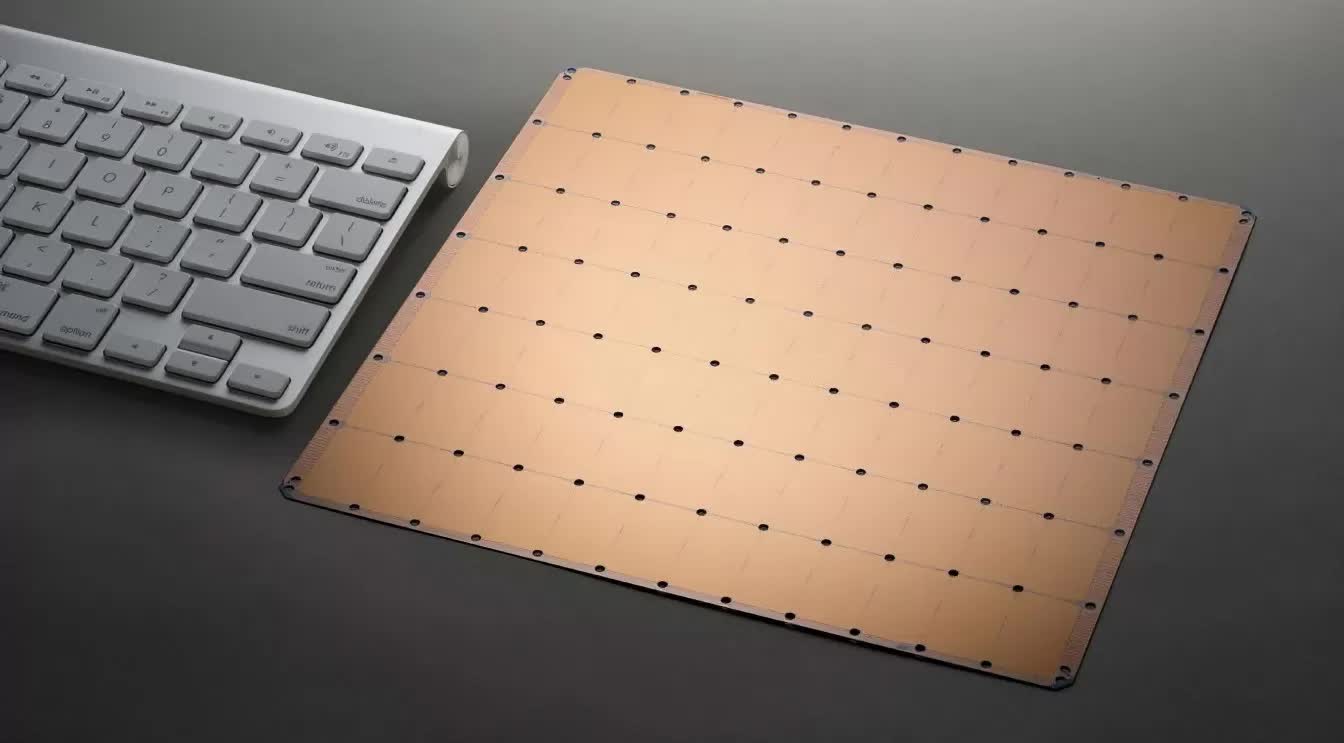

Or information technology could well be the other way round. Nvidia (and others) have done significant research into scaling GPU performance by using a modular design -- i.due east. having multiple smaller dies on the same package, much like AMD does with chiplets on Zen-based CPUs.

While such research was predominantly for the professional market, it's worth remembering that many of Volta's features found their way into Turing, so it could exist possible that gamers at the finish of this decade will have PCs sporting numerous CPU and GPU chips, all packed into relatively compact packages.

Simply regardless of what format they take, tomorrow'southward GPUs will go along to push the boundaries of VLSI chip design and microprocessor fabrication. The raw capabilities of futurity GPUs in terms of FP32 throughput and internal bandwidth will reach levels that could only be dreamed almost, just 10 years ago.

And with Intel and others determined to forcefulness their way into the market, to capitalize on the growth of GPGPU in AI, we can be sure of ane matter: AMD, Nvidia, et al are all nonetheless many years away from reaching the limits of what they can reach with their graphics processors.

Source: https://www.techspot.com/article/2176-history-of-the-gpu-part-5/

Posted by: puckettblegifter96.blogspot.com

0 Response to "History of the Modern Graphics Processor, Part 5"

Post a Comment